KATHRYN JEAN LOPEZ….AN INTERVIEW OF BING WEST AND DAKOTA MEYER…..MUST READ ****

http://www.nationalreview.com/articles/330814/dakota-hero-interview

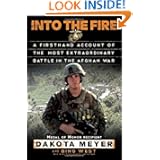

Bing West has written Into the Fire: A Firsthand Account of the Most Extraordinary Battle in the Afghan War with Marine Medal of Honor recipient Dakota Meyer. Days before the final, foreign-policy-focused debate between presidential candidates Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, West talks about the book and Afghanistan with National Review Online’s Kathryn Jean Lopez.

KATHRYN JEAN LOPEZ: In the book, Dakota Meyer recalls: “Sometimes you do think about it. That tiny figure in the distance is a human being. He may be a great guy, or he may be one of those animals who will beat his sister to death for having a boyfriend not arranged by the family. You are not there to judge. My only job is to bring him down before he gets to cover.” What does that do to a man in the short and the long term?

BING WEST: Every Marine is a rifleman. You do one thing with a rifle. Dakota — an experienced sniper — was lethal in the Ganjigal battle because he cycled through five weapons (and a rock) without having to think. He had “muscle memory,” like a professional baseball player up at bat. In the short term, he was a killing machine. In the medium term, he was torn up about not having reached his team in time. He has told me he does not dwell upon those he killed, except to want to kill more terrorists.

LOPEZ: “In the hills along the Pakistani border, no Afghan, military or civilian, had much of anything,” Dakota remembers. “I think practically every American soldier or Marine tried to help in some way. . . . Maybe a decade from now, some kids would remember that some Americans were kind to them, even when their older brothers were shooting at them. Maybe not. You don’t help out because you expect something in return.” Will history remember this? Should it?

WEST: I think Dakota had it right. You help others because it is the right thing to do, period.

LOPEZ: “The focus of this book is the character growth of Dakota Meyer. His story stands as a metaphor for the war,” you write. “It illustrates three themes: a frustrating war, a misplaced strategy, and the grit of the American warrior.” What can we take from it as a concrete lesson?

WEST: First, our national hubris a decade ago caused terrible policy. Our president, our Congress, our press, and the rest of us fatuously believed we had a trillion spare dollars to build democratic nations in the Islamic Middle East. National conceit led to irrational exuberance about impossible tasks.

Second, our generals concocted a wacky theory of benevolent warfare. Instead of killing the enemy, we would convert them and win the hearts and minds of tribes hurtling headlong into the ninth century. Therefore our generals, year after year, tightened Rules of Engagement that placed our troops at higher risk, diminishing their morale and their willingness to patrol aggressively.

Third, courage remained, as Aristotle wrote, “that quality that makes all other qualities possible.” Iraq and Afghanistan demonstrated that America has the right stuff in its warriors like Dakota, youths who volunteer year after year. I’m not writing fluff; in many other Western nations, the spirit of the warrior is flickering out. That is not the case in America. Seventy-five percent of our force is made up of four-year volunteers like Dakota who serve and return to civilian life. Little is written about them. There are 400 books about SEALs on Amazon — more than the number of SEALs in Afghanistan. Our Special Operations Forces are tremendously special because they are lifetime professionals. We cannot, however, have a lifetime professional military because eventually everyone is 60 years old. We need the spirit of the Dakotas — they are the heartbeat of our military.

LOPEZ: What do you hope to accomplish in the telling of Dakota Meyer’s story?

WEST: Dakota was the bravest American because he attacked in the face of certain death — he believed it was only a matter of time until he died — not once, not twice, but five times over the course of five hours. I wanted Dakota to tell us his story because I was fascinated by the basic question: Was it Dakota’s nature before he enlisted, or the nurturing and training of the Marine Corps that caused him to attack and attack when others would not?

I leave it to the reader of Into the Fire to decide the answer!

LOPEZ: Why is Ganjigal so important?

WEST: Ganjigal illustrated the maddening and conflicting loyalties of the Afghans, the grit of our troops under intense pressure, and the consequences of a high command that issues Rules of Engagement that permit staffs off the battlefield to make life-and-death decisions.

LOPEZ: How should history remember Lieutenant Michael E. Johnson, Staff Sergeant Aaron M. Kenefick, and Corpsman 3rd Class James R. Layton?

WEST: Even in death, the team stayed together for each other.

LOPEZ: The late Afghani Dodd Ali is an important part of the story of Dakota Meyer and Afghanistan, isn’t he?

WEST: Dodd Ali symbolized the goodness, likability, loyalty, and bravery of the Afghan farmer turned soldier. Dodd Ali never flinched.

LOPEZ: Why is it so important that Army Captain William Swenson receive a Medal of Honor?

WEST: Army Captain William Swenson took command when others choked. He was recommended at the battalion and the brigade level for the Medal of Honor, together with Dakota. Yet at the Army general-officer level, the recommendation was “lost” for two years. This is an institutional disgrace the Army must rectify.

LOPEZ: How would you hope Americans might think about the war in Afghanistan? About the Afghan people? About our Americans who have died in Afghanistan?

WEST: It’s too early to know how Afghanistan turns out internally. It’s not too early to observe that we have achieved our basic goal: preventing Afghanistan from being a sanctuary from which terrorists can again attack our civilians.

LOPEZ: Is there anything every voter ought to consider from Dakota Meyer’s story before he votes?

WEST: Standing tall is the best course for America.

LOPEZ: Why do you keep going back to Afghanistan?

WEST: Someone has to tell the story of the grunts from the perspective of a grunt. A grunt over the course of a seven-month deployment carries 95 pounds on his back on a hundred patrols, walking one million steps through dirt laced with mines that take your life or your legs. One million steps. Someone has to go with them and report back.

LOPEZ: You understand all too well why the suicide rate is so high among veterans. What can be done? Not just by the federal government but local communities?

WEST: Too complicated for me to venture an answer.

LOPEZ: Does it bother you that most of the country doesn’t serve in the military and has no real connection to it?

WEST: Today, we don’t have a spirit of shared sacrifice. Neither President Bush nor President Obama as the commander-in-chief understood that his role was to inculcate a feeling of togetherness when we go to war. However, our nation has matured tremendously since the Vietnam days when we in uniform were not welcomed when we returned home. In the past decade, our nation has done a terrific job of supporting our troops. Terrific.

LOPEZ: It seems such a 101 question, but you’re in a unique position to reflect on it: What is freedom?

WEST: I cannot improve upon life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

— Kathryn Jean Lopez is editor-at-large of National Review Online.

Into the Fire: A Firsthand Account of the Most Extraordinary Battle in the Afghan War by Dakota Meyer and Bing West (Sep 25, 2012

Comments are closed.