WHO IS MO YAN WINNER OF THE NOBEL PRIZE FOR LITERATURE? TWO OPINIONS

http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/authors-debate-merits-of-nobel-prize-for-chinese-writer-mo-yan-a-861381-druck.html

A Controversial Choice for this Year’s Literature Prize

Since the announcement on Thursday that the Chinese author Mo Yan, 57, has been selected as this year’s recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature in Stockholm, a debate has been raging over the Nobel Committee’s decision. The literary importance of Mo Yan is vaunted by many of his fans, but what detractors view as an uncritical and submissive attitude toward the state power in Beijing has been harshly condemned by dissidents. In interviews with SPIEGEL, Chinese author Liao Yiwu, 54, the recipient of this year’s Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, criticizes his contemporary. Meanwhile, German novelist Martin Walser, 85, gives Mo Yan’s work the highest praise.

SPIEGEL: How do you feel about writer Mo Yan winning the Nobel Prize in Literature?

Liao Yiwu: I am stunned. To me it is like a slap in the face. Two years ago I was on the train from Berlin to Frankfurt when I heard that the Nobel Peace Prize had been awarded to my close friend, the writer Liu Xiaobo, who is imprisoned in China. I was delighted — to me it was confirmation that universal values and a moral code do exist, and that the point of the Nobel Prize is to encourage writers to stand up for this moral code. Last Thursday I was once again on the train from Berlin to Frankfurt when I heard that the Nobel Prize for Literature had gone to Mo Yan. He is a state poet. I am utterly bewildered. Do these universal values not exist after all? Are they so arbitrary that a Nobel Prize can be awarded to someone behind bars and stripped of their rights one year and another year to someone in the service of the very people who put people behind bars and strip them of their rights?

SPIEGEL: Do you not make a distinction between a peace prize and a literature prize?

Liao: To me the truth comes first and then the literature. We in China are dealing with a dictatorial system and we writers have to take a stance on it. What stance does Mo Yan take? He is an example of how a regime can influence writers. He contributed to a volume of calligraphy that was a tribute to Mao. To me that shows that the truth is not his first priority.

SPIEGEL: Do you know him personally?

Liao: Yes, he once visited Chengdu and we met there. After that there were a number of opportunities for us to meet but he always avoided me. He knows that he represents a superficial China, one that can seem very glossy. Whereas I stand for a grassroots China, its dregs, its dirt.

SPIEGEL: Mo Yan might be relatively conformist but his work is not uncritical.

Liao: When push comes to shove, Mo Yan retreats to his world of artistry. That way he places himself above the truth. I don’t like that. If you are going to stick to the truth then you need to keep your distance from the Chinese government and indeed to any form of politics, including the politics of democratic countries. When China was the guest of honor at the Frankfurt Book Fair three years ago, Mo Yan was part of the official delegation. He was a symbol of the Communist Party of China’s culture. He does not keep his distance.

SPIEGEL: The awarding of the prize to Mo Yan can nonetheless be seen as a call to examine China. Is that not itself of value?

Liao: No, it is not. What has happened is very damaging, a woeful example of the West’s fuzzy morals. Chinese officials feel vindicated in the way they have treated and continue to treat dissidents by such awards. And that is terrible for the people who suffer under them. You have no idea how much the news has angered my friends in China. One musician wants to organize a protest. They are upset and asking whether the West is not in fact an extension of the Chinese system.

SPIEGEL: You yourself were awarded the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade this year. That sent a different message to the Chinese establishment — that it needs to reconsider the way it treats the disenfranchised.

Liao: Yes, party officials were extremely annoyed and that goes to show how effective a prize can be. I am pinning my hopes on readers, civil society, people who are seeking the truth. I have been living in Germany for one year and my impression is that people here are on a quest for the truth, they have come to terms with the injustices of the past, there are memorial centers and remembrance projects. Germany is my spiritual home.

Interview conducted by Susanne Beyer. Continue to the next page to read the interview with Martin Walser.

‘Orgies of Exactitude’

SPIEGEL: Mr. Walser, you are not only a huge admirer of Mo Yan’s novels — you are also strongly impressed by him as a person. When did you first meet the author?Walser: At the end of 2009 in Beijing when I received a literature prize there.

SPIEGEL: What was your impression?

Walser: I first saw him on the street, a small alley, where he arrived in the evening on his bicycle shortly before the awards ceremony at the Goethe Institute. In the darkness with a bicycle compared to which our bikes must look like utopian vehicles. That touched my heart. Later we sat together in a corner and I felt unbelievably comfortable with him. My Chinese interpreter Huang Liaoyu translated, but time and again we enthusiastically forgot that we were speaking different languages. And that we both so heartily smoked, that was nice.

SPIEGEL: What did you like about your colleague?

Walser: When you sit in front of him and think about his novels, then it seems unimaginable that this mild mannered man could produce such orgies of exactitude and savageness and beauty. He doesn’t wear that on his sleeve, he doesn’t show that in his face or in his gestures. His presence is extremely reserved.

SPIEGEL: Your enthusiasm of him, however, is anything but reserved.

Walser: It is something wonderful when one can love another author. That happens so rarely, without any kind of misgivings that authors often have between each other. It is a good fortune, when you can adore, when you can love, when you can find something so magnificent.

SPIEGEL: You were well acquainted with Mo Yan’s novels before you met him in person. What fascinated you about them?

Walser: I have never read another author who explains so much history in a present day plot. It is literature, but is also informative about a country and its pasts. Mo Yan describes everything historical in full sensory detail, not as statements but as expressions.

SPIEGEL: What do you mean by that?

Walser: His novels have a forcefulness and a richness hard to describe with simple words. All noteworthy novels describe conflict that people incur when their feelings, even their whole existence becomes subjugated to prevailing norms. However, the way that people in Mo Yan’s novels eat, drink even how they are hungry and thirsty, how they speak, love and die, it makes one dizzy. A good novelist loves all of his characters, he lives in them, even in those who commit or must commit terrible acts. If one talks about China today, then he should first read Mo Yan’s novels, which, for me, reach the level of Faulkner.

SPIEGEL: Are there parts of his novels that have stayed with you?

Walser: In the novel “Garlic Ballads,” a young pregnant woman hangs herself the moment she begins to experience labor pains. I’ve never read a harsher occurrence in any work of literature. Compared to that, Medea is a kindergartener. The woman is in conflict with all powers, even her own family. Her beloved dies with a police bullet to the back. She finds her end on a beam after all these experiences of intimacy and brutality. And the poetry, even the comic elements of the novel, in no way tone down the relentlessness and harshness of the event. Every detail is both beautiful and gruesome at the same time. It is at all even readable because it is beautiful. One asks himself at times, why he so voraciously devours it.

SPIEGEL: Dissidents accuse Mo Yan of being too close to the state. Can you understand that?

Walser: What is in Mo Yan’s novels about the state of China today, its functionaries and its party, appear to me to be extremely critical and open. That he can write all of that is astounding. I have heard that even though there have been attacks against him by short-sighted party members, but his books are still getting printed.

SPIEGEL: Mo Yan’s initial reaction to receiving the Nobel Prize was very reserved. He reportedly said that he was very happy but that he didn’t believe the prize would have that much meaning.

Walser: I believe that about him. That shouldn’t sound arrogant, but for us people in the West the Nobel Prize for literature probably has a bigger meaning than for him and other Chinese. One can only hope that many people, everywhere in the world will now read his books.

Interview conducted by Volker Hage

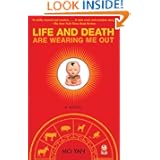

Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out: A Novel by Mo Yan and Howard Goldblatt (Jul 1, 2012

Comments are closed.