The New York Times vs. RealClearPolitics THE 1735 PROJECT, PART 5 Carl Cannon

Ten days after the 2020 election, Tom Bevan, co-founder and president of RealClearPolitics, received an email from a New York Times reporter who covers the media. The reporter, Jeremy W. Peters, advised Bevan that his newspaper was working on a story about RCP and asked for responses to various questions and accusations. Four days later, Peters’ critique was published under the headline “A Popular Political Site Made a Sharp Right Turn. What Steered It.”

The sleight-of-hand was right there in the headline. The New York Times simply declared that RCP “made a sharp right turn,” and suggested it will document how this happened.

The Times’ story asserted that during the period of counting absentee and late-arriving mail-in ballots, RCP took three days longer than other news organizations to call Pennsylvania for Joe Biden. It noted disapprovingly that we aggregated stories from other news outlets quoting Trump supporters who questioned the election results. It suggested that the RCP Poll Averages were manipulated to be favorable to Donald Trump. Peters focused on RCP staff layoffs in September 2017, and claimed we’d hired partisan Republicans to replace them. He reported that the RealClear Foundation, a nonprofit that supports our journalism, receives contributions from conservative donors. He also called into question a RealClear Investigations exposé naming the whistleblower whose complaints led to Trump’s first impeachment.

Jeremy Peters declined to be interviewed for this rebuttal, though he was courteous about it. Nor did he reach out to me in 2020, beyond contacting Tom Bevan. It didn’t hurt my pride, but I’m the most experienced newsman at RCP; I oversee our original content, I direct our reporters, and I have written more words for RealClear than anyone else.

Nor was there any bad blood between me and the “paper of record.” In the 1980s, the Times credited my groundbreaking coverage of the Catholic Church sex abuse scandal. In the 1990s, Howell Raines tried to hire me. Three books I’ve co-authored have been positively reviewed by the Times. When I covered the White House for National Journal, the Times’ book editor asked me to review a book about Dick Cheney. I have had friends at that newspaper. Although I’m not famous, I’m not unknown in Washington journalism. What I’m best known for is being relentlessly nonpartisan. If someone is writing about bias at my organization, calling me would have been the obvious place to start.

I shouldn’t have waited three years to respond to the Times but will do so now.

‘Rightward Turn’ and Post-Election Coverage

The thrust of the Nov. 17, 2020, Times article was that RCP had “taken a rightward, aggressively pro-Trump turn over the last four years.”

Here is one passage:

As the administration lurched from one crisis after another – impeachment, the coronavirus, a lost election the president refuses to concede – Real Clear became one of the most prominent platforms for elevating unverified and reckless stories about the president’s political opponents, through a mix of its own content and articles from across conservative media.

In recent days, as Mr. Trump and his loyalists repeated baseless claims of rampant voter fraud and counting errors, Real Clear Politics gave top billing to stories that reinforced the false narrative that the president could still somehow eke out a win. Headlines on Monday – more than a week after Mr. Biden had clinched the race – included “There’s Good Reason Not to Trust Election Results” and “Trump Attorney Says Results in Several States Will Be Overturned.”

I went back and searched for those two headlines, both of which appeared on RCP on Nov. 16. The first was a link to an opinion piece from a conservative outlet, The Federalist. The second was a news story from the Washington Examiner posted on the left column, the section where we post breaking news. It ran between two other stories, “National Security Adviser Vows ‘Professional Transition’ of Power” and “Biden Turns Up Pressure for Administration Recognition.” In other words, it was part of a roundup of what was happening in both camps in the election aftermath. My review of the RCP front page for that period (and readers are free to look for themselves) shows balanced coverage of a heated debate taking place in the days after a very contentious election.

Peters wrote that we gave “top billing” to stories reinforcing the “false narrative” that Trump could eke out a win. That is a distortion: The Trump campaign launched a series of legal battles in several states, and we ran stories and opinion pieces reflecting that development, from both a Democratic and Republican perspective.

We did, however, give top billing to two of Jeremy Peters’ own colleagues. On Nov. 12, the top item on the RealClearPolitics front page was a column by Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times headlined “When Trump Vandalizes Our Country.” Four days later, the top piece on the RCP front page was an op-ed by Charles Blow titled “Trump, the Absolute Worst Loser.”

Overall, RCP ran 374 news stories or opinion pieces on our front page between Nov. 4 (the morning after the 2020 election) and Nov. 17, the day the New York Times went after RealClearPolitics. Sixteen of them were from the New York Times itself, including two columns from Maureen Dowd and one from Paul Krugman. The rest were a mix of news and opinion, from outlets ranging from those on the liberal side (The New Yorker, The Nation, Slate, etc.) to the conservative outlets (Washington Examiner, The Federalist, the Daily Caller, etc.) and everything in between, including CBS News, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, Politico, The Hill, and many more. Our assurance to readers has always been to present all angles and perspectives of political events, a promise we have kept.

The simple fact is that the amount of liberal material published in RCP every week dwarfs the annual conservative content in the New York Times. This is a newspaper where columnist Bari Weiss was bullied into resigning and editorial page editor James Bennet was fired in response to demands from leftist activists on the paper’s staff. It’s happened to others at that paper, too. The Times’ criticism of RCP, in other words, seems to be a classic case of psychological projection. We tolerate diverse voices where I work. We encourage it. It’s our business model and our belief system.

Calling Pennsylvania

In both his email to Tom Bevan and his Nov. 17, 2020, story, Jeremy Peters questioned RCP’s decision to wait until a week after Election Day before moving Pennsylvania into Biden’s column on our election maps. CNN, CBS, ABC, and the Associated Press called the state before noon on Saturday, Nov. 7 – and with it the 2020 election. Biden held a 34,000-vote lead in Pennsylvania with 62,000 absentee ballots still to count, along with an estimated 100,000 provisional ballots. The consensus was that Trump couldn’t make up the difference. This turned out to be right. Biden ultimately won Pennsylvania by 80,555 votes.

Should RCP be faulted for taking a cautious approach? Journalism is a competitive field, and we want to get the news out first, hence the headlong rush to “call” elections for one candidate or the other. But not at the cost of getting it wrong. The most famous erroneous call came in the 1948 presidential election, an embarrassment seared into the institutional memories of political writers. It’s not the only example. Premature media calls in 2000 shortly after 2 a.m. the night of the election led to a premature concession phone call from Al Gore to George W. Bush. In 2020, the same election the New York Times was writing about when it criticized RCP, Fox News was embroiled in controversy for declaring Biden the winner in Arizona before those results were truly settled. Fox analysts ended up being right in Arizona, but not before Biden’s large early lead Election Night dwindled to 10,457 votes out of 3.3 million votes cast. The Arizona drama underscores a basic fact: Such media predictions don’t have any legal force and effect. The actual vote-counting is done by the states.

In that context, our discretion in Pennsylvania can be seen as a virtue, not a fault. We didn’t pretend to know more than we did, and we provided our readers with every bit of information at our disposal in real-time. This data certainly didn’t trend in the Republicans’ direction. Our preelection maps had Biden carrying Pennsylvania, and we kept the state’s running vote tallies on our front page each day as the ballots were counted by the state. Any RCP reader could see that Biden was winning and that his lead was increasing. Yet here is how the Times characterized it: “[RCP’s] delay was welcome news to allies of President Trump like Rudolph W. Giuliani and friendly outlets like The Gateway Pundit, which misrepresented the site’s decision in their efforts to spread false claims that Mr. Biden’s lead was unraveling.”

It’s hard to fathom how anyone would blame us for Rudy Giuliani’s erratic statements, or the behavior of Donald Trump, who was braying about vote fraud two months before Election Day. In the example cited by Peters, Giuliani had tweeted Nov. 9 that RCP had “rescinded” its Pennsylvania call. This was false, and Tom Bevan immediately said so on Twitter.

The Times story did not accurately characterize how RCP reported on the 2020 election returns anyway. On our Nov. 6 Friday morning podcast, Bevan said that Biden had apparently won a 300-plus Electoral College victory. I added that it was clear by Thursday that Biden had won. In my Friday newsletter, I characterized Trump’s shenanigans as a “temper tantrum” and wrote “if a candidate alleges that a presidential election has been stolen from him, it is incumbent on that candidate to produce evidence – and fast.”

“Tantrum” was the same word used by Russian opposition leader Garry Kasparov in a New York Daily News column we ran on our front page the morning after the AP called the election, along with a Maureen Dowd column titled “We Hereby Dump Trump.” We also ran Trump’s own words on our front page – below the lead story from CBS on Biden’s victory speech. Our own columnist, A.B. Stoddard, wrote a Thursday, Nov. 5 piece posted on RCP’s front page with the title “No, Democrats Are Not Trying to ‘Steal’ the Vote.”

RCP didn’t provide any “welcome news” to the “stop the steal” crowd. Trump and his lieutenants were plotting how to challenge any adverse results well before Election Day and they stuck to their plan. We simply covered the election and its aftermath.

The RCP Poll Average

In his email informing Bevan of the story he was writing, Peters said he was looking into RCP’s election analyses on the grounds that they “tended to skew toward or favor Trump.” He said he was focusing on the RCP Polling Averages, “which your competitors have questioned for including Rasmussen, Trafalgar and others.”

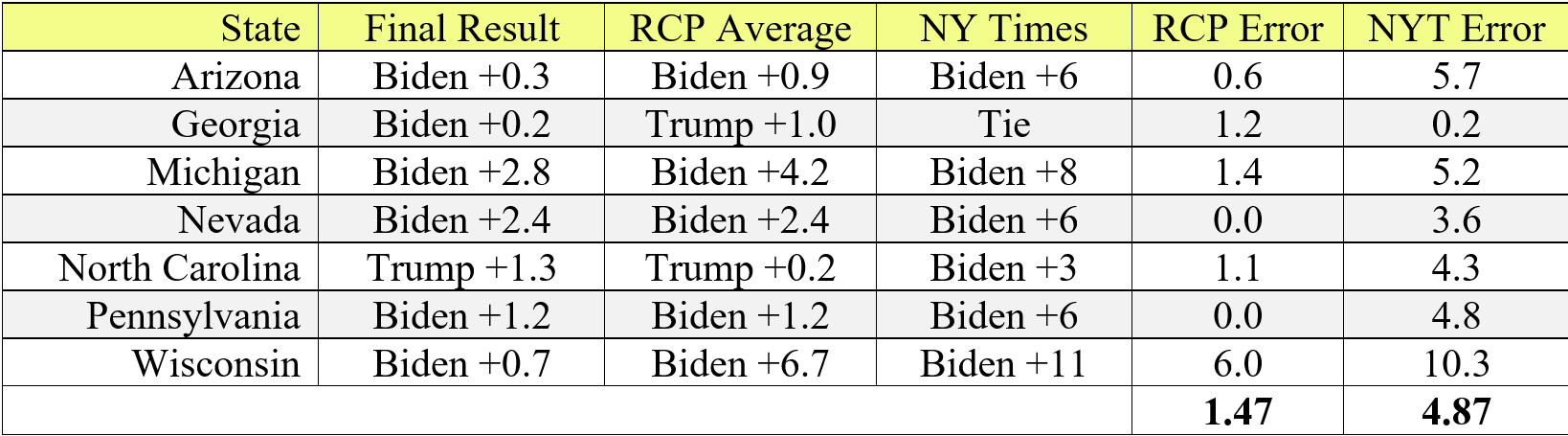

This complaint doesn’t withstand scrutiny either. First, to the degree the RCP Poll Averages favored one candidate over the other, they favored the Democrat Joe Biden more than the Republican Donald Trump. Second, in the seven closest states in the 2020 election – those decided by three percentage points or less – the RCP Poll Averages were demonstrably more accurate than the New York Times’ own poll, and it wasn’t even close.

As you can see from the chart below, in five of the seven battleground states in 2020, the Times was off by more than four points in Biden’s favor. By contrast, the error in the RCP Poll Average in those seven states was only 1.47 points – and the only reason it was that high was because the polls in Wisconsin were terribly off, including a final one by Washington Post/ABC News showing Biden leading by 17 points and one by the New York Times itself showing Biden with an 11-point lead. Subtract out Wisconsin and the error of the RCP Poll Averages in six remaining battleground states in 2020 was 0.72 points.

Take special note of Pennsylvania, the state singled out by the Times. As the chart shows, the RCP average in the Keystone State was, well, perfect. It had Biden leading Trump by 1.2 percentage points. When the votes were tallied, Biden won by … 1.2 percentage points.

RealClearPolitics also offered a feature called the “no toss-ups” map in which the Electoral College votes are assigned to whichever candidate was leading in the RCP average. Our map had the Democratic ticket of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris winning 319 electoral votes compared to 219 for Republicans Donald Trump and Mike Pence, very close to the final total.

You can go down a rabbit hole very quickly when parsing these numbers, so I’ll make two final points before moving on.

First, a discerning reader who followed the RCP averages in 2020 would have concluded both that Joe Biden held a larger lead in the national popular vote than Hillary Clinton had four years earlier and that in the battleground states where the election would be decided the race was tight, meaning that Trump prevailing in the Electoral College was a real possibility, just as it had been in 2016.

Second when all the votes were finally counted, it was clear that the polls touted by RCP’s critics were significantly less accurate than the ones they criticized. Their preferred polls were unfailingly too pro-Democratic. Was this due to incompetence? Inadvertent bias? Something else? Examining that question would have made for an interesting story. Instead, the New York Times just pretended none of it happened and disparaged a competitor.

Layoffs

In mid-September 2017, RCP laid off 20 of our 70 full-time employees, including more than half my editorial staff. It was the most painful day of my life – and that’s saying something because the year before I had lost my mother and one of my brothers. I’m sure it was much harder for the cashiered colleagues, one of whom was a close friend. I vowed to them that I’d do everything I could to find them other jobs, and I kept my word.

Here is how the New York Times characterized it: “They were never given much of an explanation why, the former employees said. But they were surprised to learn who was replacing them in some cases: writers who had worked in the conservative movement or for the Republican Party. One hire was the former chair of the Manhattan Republican Party and was married to a senior Trump administration official.”

It’s true that our employees felt blindsided by the layoffs. But the reason behind the staff cuts is no mystery to those who have closely followed the media business landscape over the last few years. RCP’s business model had always been cyclical: huge traffic spikes in presidential election years followed by leaner years that required belt-tightening (but never layoffs). In 2017, however, this pattern did not hold. For starters, there was a toxic “Trump effect.” Our ecosystem immediately became so bitter that companies which had paid for direct advertising with us in the past or had sponsored public policy forums suddenly became averse to politics – a word that is in our company’s very name.

But what was really devastating in 2017 was the collapse of programmatic ad revenue driven by Big Tech, principally Google and Facebook. Programmatic revenue, known in the business of online publishing as CPMs or RPMs, refers to the amount of money publishers could make via ads per page view. Programmatic RPMs to RealClear fell by over 75% following Trump’s election, breaking a 10-year rise of steadily higher RPMs. The extent of the collapse was unprecedented and not something remotely anticipated even one year before.

At RCP, the result was layoffs and cost-cutting. We were hardly alone. Four months before the layoffs at RealClearPolitics, the New York Times itself completed its own round of buyouts at the paper, at which time they also eliminated the role of “public editor.” (“Ombudsman” was the long-standing name at most publications, very few of which still have such an internal oversight position.) That followed a previous round of buyouts/layoffs at the Times in 2014 – as well as 2011, twice in 2009, and once at the beginning of 2008.

As to the accusation that we “replaced” our laid-off news reporters with more conservative writers, that’s not really what happened. In August 2018, 11 months after our layoffs, we hired Adele Malpass as an independent contractor to cover national politics. She was a former politics reporter for CNBC and a former chairwoman of the Manhattan Republican Party (both of which we clearly noted in her bio line) and also the wife of David Malpass, who had been appointed an undersecretary at the Treasury Department. She wrote 22 stories for us over the course of five months and left RCP in mid-January 2019.

There is an obvious double standard at play here. The number of reporters in Washington who are either former Democratic Party operatives and/or married to Democratic administration officials is too numerous to count.

In free market capitalism, those who ride to the rescue of troubled industries are not always knights in shining armor with motives as pure as Sir Galahad. New York Times employees should know this better than most. In 2009, when the Times stock price was lower per share than the cost of its Sunday newspaper, a Mexican billionaire named Carlos Slim bailed the newspaper out. At a time when he already owned 6.9% of the Times, Latin America’s richest tycoon put another $250 million into the company. The Times dutifully mentioned this fact in a press release, but as Time magazine noted in January 2009, “the press release does not mention any of the controversial parts of Mr. Slim’s past, which has to make Times editors uncomfortable.”

How had Carlos Slim acquired a fortune estimated in excess of $75 billion in a country where 43% of the people are poor? Certainly, he’s a shrewd businessman who sees around corners. He is also at the top of the pyramid in a nation where crony capitalism is king. Unlike Jeremy Peters, who casually asserted that conservatives’ donations to RealClear Foundation altered our hiring practices and news judgment, I don’t accuse the Times of pulling its punches on Carlos Slim or Latin American politics. But others have. In an essay headlined “Who is more dangerous: El Chapo or Carlos Slim?” The Guardian declared that the Times and other U.S. news organizations are reluctant to explore how Mexican oligarchs “used their power to stymie the tax policies, public investments, and income transfers” necessary to expand Mexico’s middle class.

When Peters dug into the tax filings of RealClear Foundation, he knew more about my company’s finances than I did. Until recently, I’ve made it a point not to know who donates to our foundation. I concede, however, that the financial pressure on media entities is a legitimate line of inquiry, as are their sources of revenue. I’ll also concede that journalists’ declarations of independence and incorruptibility require a leap of faith among our readers and critics.

And I recently have been enlisted in the cause of soliciting contributions myself, so that we can continue to do important work like reporting on religious freedom around the globe. That’s the environment we find ourselves occupying. And while it’s true that RealClear Foundation has had more success appealing to conservative than liberal donors, it’s not for lack of trying on our part. But I will say this: Potential donors aren’t buying coverage. Rather, they are contributing to an enterprise determined to remain nonpartisan and dedicated to the cause of presenting multiple points of view on important questions of the day.

Whistleblowers

The New York Times also took RCP to task in its Nov. 17, 2020, piece for a story in RealClear Investigations by Paul Sperry identifying CIA analyst Eric Ciaramella as the person who spearheaded the first Trump impeachment over Trump’s fateful July 2019 phone call with newly elected Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky. Here is what Peters wrote:

One article from October 2019, for instance, purported to name and identify in a photo the anonymous whistle blower who reported the phone call between Mr. Trump and the Ukrainian president that led to Mr. Trump’s impeachment. Other news organizations knew the identity but declined to publish it because of concerns that the person’s safety could be jeopardized. Facebook prevented people from sharing the Real Clear article, saying it violated the social network’s policy against inciting harm. Fox News cautioned its staff at the time not to identify the person on the air.

My response is simply that I think the New York Times, Facebook, Fox News, and all the rest are on the wrong side of this question, and not adhering to traditional journalistic norms or impulses. Whistleblower protections don’t always automatically ensure anonymity – and certainly not from the media. They mean protection from being fired or prosecuted or being subject to other professional reprisals. Launching an impeachment effort against a sitting president and hoping to keep your name out of the newspaper is a lot to ask.

As for the safety issue, that seems like a canard. During George W. Bush’s presidency, it was raised when Valerie Plame’s name was leaked. She, too, worked for the CIA and, along with her husband, also sought to undermine a Republican president over national security concerns. But Plame didn’t go into hiding. She wrote a memoir, which was made into a Hollywood movie, and later ran for Congress. Eric Ciaramella isn’t running for Congress, but Eugene Vindman, one of the other Ukrainian phone call whistleblowers, is doing so in 2024 – on this very issue.

Two months before Paul Sperry’s scoop, the Times wrote that the whistleblower was a male CIA officer who had been assigned to the White House national security team and was now back at Langley. In other words, the “paper of record” signaled that it knew his identity but deliberately chose to keep the name secret. Dean Baquet, the paper’s top editor at the time, gave this explanation: “We wanted to provide information to readers that allows them to make their own judgments about whether or not he is credible.”

How a CIA connection makes a news source automatically “credible” is beyond me. In any event, Sperry wrote that Ciaramella had previously worked with Trump-hating CIA Director John Brennan, and for Joe Biden. Sperry also reported that he had been accused of leaking negative information about Trump and was friendly with Democratic staffers who worked for Rep. Adam Schiff, the House Intelligence Committee chairman who spearheaded the first impeachment.

Ciaramella’s lawyers said none of that is relevant and that his accusations against Trump should stand on their merits. Perhaps this is true. And Sperry is a provocative conservative writer disliked by liberals. Still, nonpartisan journalists should be appalled at the lengths Democrats have gone to silence him. A year after he outed Ciaramella (and as the House geared up for the Jan. 6 commission), Sperry’s Twitter account was abruptly suspended. Five days later, on Feb. 22, 2021, a top Schiff aide pressured me to “correct” year-old stories linking Ciaramella to two Schiff committee staffers. I came away from the encounter suspecting that Schiff and his aides were involved somehow in the Twitter ban. The “Twitter Files” reporting by Matt Taibbi in January 2023 confirmed these suspicions.

My view is that the well-organized efforts by the FBI and people like Adam Schiff to pressure Twitter to censor journalists violates both the spirit and the letter of the First Amendment – and that the New York Times, of all institutions, ought to know better.

In the 2017 Hollywood film “The Post,” director Steven Spielberg chronicled how editors at the Washington Post and the New York Times bucked the White House and Justice Department – risking prison in the process – to challenge the government’s narrative about Vietnam by publishing The Pentagon Papers. The Times had gone first, then paused publication. Post editor Ben Bradlee, played by Tom Hanks, dispatches a copy boy to New York, telling him to go into the Times newsroom and see if he can find out what the competition is up to.

“Is that legal?” the young man asks.

Rolling up his sleeves, Bradlee (Hanks) growls, “What is it you think we do here for a living, kid?”

The answer, of course, is that they report the news and do so “without fear or favor,” as a great man once said.

How We Roll at RCP

RealClearPolitics started in the late 1990s when Princeton grads John McIntyre and Tom Bevan (who did not know each other in college, contrary to what Peters wrote) noticed that with the rise of the Internet an American could, for the first time, read fresh editions of the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post from their own home on the same day with only a few clicks of the keyboard. They started a website designed to be a clearinghouse for political junkies who cared about politics, policy, and elections. Their special sauce would come to consist of two ingredients: aggregating news stories and columns spanning the ideological spectrum, and averaging campaign horse-race polls.

Over time, they hired reporters and editors to do original work, including Senior Elections Analyst Sean Trende. As Bevan and McIntyre noted in a response to Jeremy Peters, Sean is a co-author of the Almanac of American Politics and is among America’s most well-respected and often cited nonpartisan political analysts.

Along the way, a slew of other “vertical” sites were added to the mix, including RealClearMarkets, RealClearScience, RealClearDefense, and RealClearInvestigations. (Tom Kuntz, RCI’s editor, worked as a New York Times reporter and editor for 28 years.)

In 2018, we launched RealClear Opinion Research to do our own surveys – though not horse-race polling. John Della Volpe, a highly respected Democratic pollster from Boston, launched the effort. His first poll was an in-depth look at the electorate that he divided into “five tribes.”

The following year we launched a book publishing arm. RealClear Publishing’s first title was “Contract to Unite America: Ten Reforms to Reclaim Our Republic” by Neal Simon, who had run for the Senate in Maryland as an independent. Our second book was a call for universal basic income, by Steven Shafarman, who fleshed out a key theme behind Andrew Yang’s presidential campaign. For Women’s History Month in 2020, we published a daily feature by Dana Rubin highlighting American women speaking out on important issues. That series was the inspiration for the book “Speaking While Female: 75 Extraordinary Speeches by American Women” – the publishing project that gave me the most satisfaction. And though it wasn’t the point, I’d note that most of those 75 speeches were progressive calls to action. Does any of this sound remotely like a news organization that “made a sharp right turn”?

Here’s how we actually do things: When Mitch McConnell announced he would step down as Senate Republican leader, I touched base with veteran journalist Howard Fineman, one of our accredited writers. Howard, who covered McConnell back in his Louisville newspaper days, dashed off a blistering elegy taking McConnell to task for remaking the federal judiciary in a decidedly rightward direction.

The next day I noticed that Grover Norquist, a prominent small-government conservative, had lauded McConnell on Twitter. I asked Grover if he could expand his thoughts into an op-ed. So we published two opposite viewpoints, both from people who know what they are talking about.

The same week, I found the coverage of President Biden’s reelection chances was getting too negatively one-sided. In 2022, Democratic consultant Maria Cardona wrote an op-ed for RCP that was bullish on the Democrats’ chances of blunting the predicted Republican “red wave.” So I sent her a note asking if she knew anyone who could write a column advising Democrats not to panic about Biden’s reelection chances, hinting that she herself might do it. “With my eyes closed,” she replied. Maria delivered, too.

Earlier this year, my old friend Les Francis submitted a column he co-authored with Frank Donatelli. Les is a California Democrat I’ve known most of my adult life who worked for the great Norman Mineta and in the Carter White House. Frank Donatelli is a longtime Republican loyalist and former Reagan administration official. I wasn’t aware they even knew each other, but one day their joint op-ed showed up in my inbox. It was a screed against the presidential machinations of No Labels, the gist of their argument being that the two-party system has served the country “pretty well” for 250 years and this was no time to fool around with an untested idea.

I was traveling and didn’t get back to them quickly, but Francis tracked me down. He asked about the piece, which I was lukewarm about. “Les,” I said, “I pretty much disagree with every word in that piece except your bylines.”

Les knows me well. “So that means you’ll run it,” he said with a laugh.

“Yes,” I said. And we did.

Uncharted Waters

This willingness to quote or showcase viewpoints with which we personally disagree is how I was raised in our profession, along with most journalists of my generation. The New York Times and most of the media agreed in principle, if not always in practice – at least until Donald Trump arrived on the scene.

In a widely circulated August 2016 column, Times media critic Jim Rutenberg provided a window into the dilemma felt by many journalists, not all of whom were liberal:

If you’re a working journalist and you believe that Donald J. Trump is a demagogue playing to the nation’s worst racist and nationalistic tendencies, that he cozies up to anti-American dictators and that he would be dangerous with control of the United States nuclear codes, how the heck are you supposed to cover him?

Rutenberg noted that reporters and editors who viewed the prospect of a Trump presidency this way would instinctively “move closer than you’ve ever been to being oppositional.” Although his argument was nuanced and Rutenberg acknowledged how alienating it might sound to those who disagree, many in the press corps took it as a license to stop pretending to be objective when it came to the Republicans’ 2016 presidential nominee. The basic point here is that some journalists do not feel obliged to treat Trump the same as other presidential candidates because he is simply unlike anyone who came before him.

I understand the argument, but that word “oppositional” proved problematic. As things played out – Trump won in 2016, for one thing, and is running again now – it turned out to be a short step for the journalists who openly declared their opposition to Trump to start viewing journalists who didn’t share their perception as adversaries. It was in this context that Rutenberg’s colleague Jeremy Peters described my news organization this way:

Real Clear’s evolution traces a similar path as other right-leaning political news outlets that have adapted to the upheaval of the Trump era by aligning themselves with the president and his large following, its writers taking on his battles and raging against the left.

I submit to a candid world that it was the New York Times that adapted to the upheaval of the era by “raging” against those with whom they disagree. Facing the dreaded specter of a Trump presidency and caught in the maelstrom of a precarious business environment, the Times and many in the legacy media embraced a highly subjective, even partisan, approach to covering the news. This was the real “evolution” that took place, and it represented a radical departure from the values and traditional customs of modern American journalism.

By contrast, RealClearPolitics covered the duly elected president of the United States – chosen by the American people in a system that has lasted for more than two centuries – as we have covered other politicians and policy issues left, right, and center.

We didn’t veer one way or the other. We stayed the course.

Carl M. Cannon is the Washington bureau chief for RealClearPolitics and executive editor of RealClearMedia Group. Reach him on Twitter @CarlCannon.

Comments are closed.