Kay S. Hymowitz: Barbie’s Checkmate Greta Gerwig’s film is outfitted with so many layers of irony as to disarm the doll’s—and the film’s—most ardent critics.

https://www.city-journal.org/article/barbies-checkmate

I know. You’ve had it up to here with Barbie. You don’t care about the stunning $162 million global record-breaking opening weekend. You roll your eyes at the Barbie luggage, the candles, the ice cream, the Airbnb listing, the NFTs. You’re sick of the whole “women are so oppressed yet so wow.” You’ve heard it a million times already; the future is female.

Well, you may not be interested in Barbie, but Barbie—or more precisely, Mattel, Barbie’s corporate puppet master—is interested in you. Young children are Mattel’s core customers, but the company has set its sights on a much wider market. It sees the movie as a way for everyone—“teens, young adults, moms, glammas [a portmanteau for glamorous grandmas]” to “engage in the franchise,” in the words of Richard Dickson, Mattel’s former president and COO (now CEO of clothing retailer Gap).

Judging from the pink tsunami of the past few weeks, Mattel’s efforts are paying off. We shouldn’t be surprised. The movie is only the latest in a long series of brilliant chess moves confirming Mattel’s place as the World Champion Grand Master of marketing to progressive, relatively affluent, sophisticated consumers. I don’t know whether the company or the movie are actually as woke as some are grumbling, but I do know Mattel saw the sales potential of the woke phenomenon when Nikole Hannah-Jones was still in elementary school.

Consider Barbie’s origins. For much of commercial toy history, baby dolls were your basic girl toy. Girls would pretend to bottle-feed, dress, and comfort their dolls in imitation of their housewife mothers, who, in turn, tended to their real-life average of five (!) children. The end of the baby-doll era came in the late 1950s, after Ruth Handler, along with her husband Elliot, a founder of the young Mattel company, had a eureka moment. During a visit to Germany, she spotted an unusual doll known as Bild Lilli in a shop window. Based on a risqué comic book character, Lilli was mostly sold in tobacco shops. The character was something of a floozy, with many R-rated adventures. At the time, Lilli was coveted not by little girls but by grown men, though exactly what they did with the dolls no one was saying. To create Barbie, Mattel desexualized and Americanized Lilli, giving her a California glow, evening out her dramatically arched eyebrows and toning down her red, puckered lips. One other seemingly trivial but significant change: Lilli’s shoes were molded to her invisible feet; Barbie’s shoes are removable.

Director Greta Gerwig’s movie opens with a hilarious take on Barbie’s arrival in the U.S. market. A gargantuan doll dressed in a zebra-striped bathing suit and sunglasses suddenly appears, monolith-like, astride a group of sad-looking young girls. Dressed in dowdy, Amish-inspired smock dresses, they are awestruck at this vision of adult sexiness and glamour and immediately smash their baby dolls in angry disgust, a scene that Gerwig gleefully sets to the majestic orchestral opening of Richard Strauss’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, made famous by Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The joke, which sets the knowing, playful tone of the movie, is only slightly exaggerated. Barbie’s arrival on the cultural scene represented a momentous transformation in child’s play and gender history. Girls, who like all children are titillated by the mysteries of adulthood and especially adult sexuality, were enthralled by Barbie. Their mothers, not so much. Sensing the Mattel toy’s subversive power, they looked warily at the doll’s breasts and curves, her long legs made shapelier by her removable and replaceable high heels. An adult doll threatened their efforts to protect their children from the bitter complexities that emerged after a brutal Depression and World War. Alas, America’s doting, postwar, middle-class parents were no match for their Dr. Spock-influenced boomer children. Despite misgivings, they swarmed the toy stores to buy Barbies for their children. It was no use fighting such a cultural force.

The year was 1959. A year later, the birth control pill would come on the market and change women’s lives dramatically. It’s no stretch to say that, by introducing the adult albeit somewhat de-sexualized doll, Mattel helped to usher in the 1960s. True, Barbie was not straightforwardly sexual; she was famously made sans vagina. Her boyfriend Ken, introduced in 1961 after girls demanded that Barbie have a love interest, is also as clean cut as Beaver Cleaver. (In developing Ken, Ruth Handler, who had already shown herself willing to bring a hint of the forbidden to the toy chest, wanted to give Ken a bulge at his crotch, but her colleagues vetoed the move.) In any case, despite her breasts, Barbie was still virginal, though somewhere between teenager and adult woman and at her peak of unspoiled ripeness, living a life of leisure and fun. The baby doll industry—and, it sometimes seemed, the entire toy trade—was vanquished.

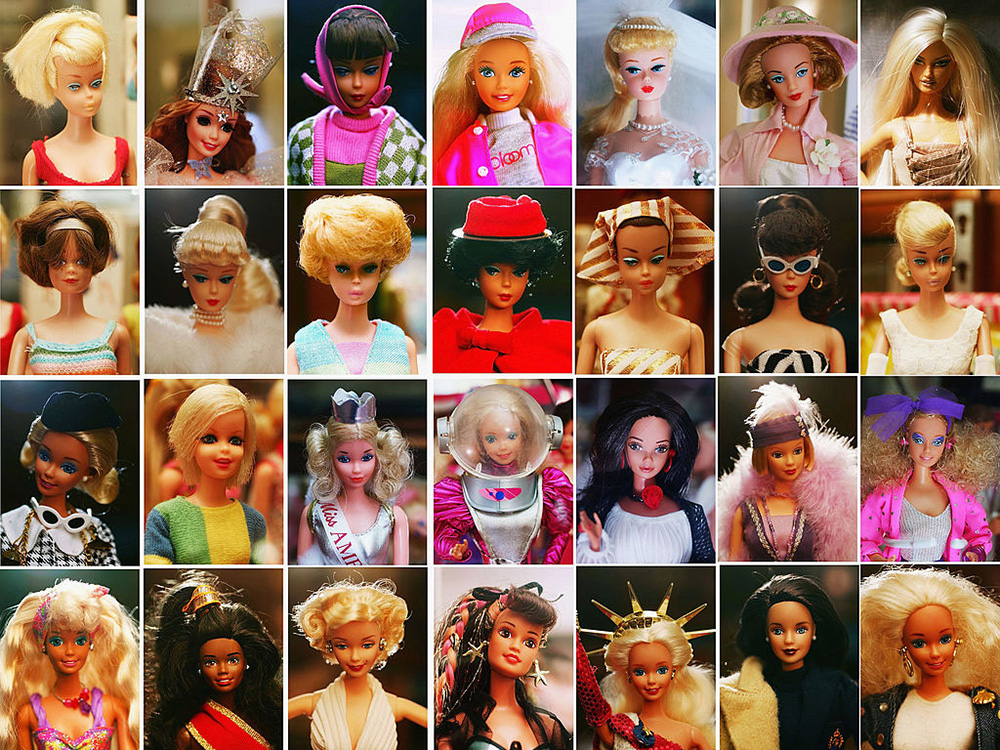

At least for a while. Mattel had won over skeptical mothers, but within a few years the company was contending with another hostile force. As second-wave feminism spread, so did Barbie hate. Where little girls saw forbidden adult secrets, sparkly clothes, and glamour, feminists saw impossible beauty norms, anorexia, and low self-esteem. Barbie was teaching girls to be airheads, they objected, interested only in clothes, shoes, and looking sexy. Mattel was three steps ahead of them. They would change the brand by sending Barbie to the office! They would show that Barbie could be a role model not as a sex object, but as a career woman who could “inspire the limitless potential of girls.” She would be “aspirational”—that is, she would teach girls about all the opportunities open to them. (All opportunities, that is, except motherhood: unlike mothers, working women can’t sit around in sweatpants and aprons all day. Barbie’s pregnant friend Midge was one of the company’s few missteps, especially her creepy magnetic belly attachment with a baby inside. Midge was almost immediately taken off the market.) The company claims that Barbie has had 200 careers, including fashion designer, lawyer, doctor, ballerina, pilot, paleontologist, chef, political candidate, and even president.

It seems obvious that Mattel also quickly recognized that, whatever her aspirational meaning, Working Barbie was a fantastic brand extension. She would need lots of accessories: briefcases, eyeglasses, power suits, pocketbooks—and more shoes, of course. Thanks to Ruth Handler’s minor alteration of slutty Lilli’s feet, you can dig through any landfill in the world, and you’re bound to find a stray tiny plastic high heel. The truth is, Barbie has always been a mannequin for displaying the real product: her possessions. She began her life in a booming postwar economy with an impressive 22-piece wardrobe selling for one to three dollars. As Handler recalled in her 1994 memoir, “It was the razor and the razor blade theory: sell the razor at a reasonable price and people will buy the razor blades—or clothes, in our case—to go with it.”

Gerwig’s Barbie could march for equal pay and stay gorgeous. She has enormous fun with the world that Barbie, Ken, and her friends inhabit in the film: Barbieland, a brilliant mixture of physics-defying cartoon artifice and actual humans. Unlike the Real World—as the movie terms its questionable vision of life as we humans know it, and where Barbie will soon discover that men are in charge—girls run everything in Barbieland. While Barbie flourishes, Ken has nothing going for him. We know that he hangs around in bathing suits a lot, but he isn’t a lifeguard. He just “does beach,” in the movie’s comical parlance. In the end, Ken, perfectly played by a buff Ryan Gosling, is Barbie’s arm candy, another one of her accessories. Even his good looks are useless in a girl-powered Barbieland: “I’m just Ken. Anywhere else I’d be a ten,” he sings mournfully.

In the decades since Barbie entered the workforce, Mattel has continued to outwit its increasingly progressive and affluent critics, all while expanding its customer base. The company’s website has an entry describing its “Diversity Evolution” as it adapted to changing demographics and attitudes. Black Barbie and Teresa, “Barbie’s Hispanic friend,” were introduced in 1980. Before that was Christie, Barbie’s black friend, which first sold in 1968. The company boasts that Barbie now comes in 35 skin tones and nine body types, making her the most “diverse and inclusive doll line on the market today.” Its most recent gesture to the zeitgeist is trans Barbie, introduced in 2022, and a trans actor appears in the movie. It’s fitting in one way: trans Barbie doesn’t have a vagina, either.

Gerwig’s Barbie continues Mattel’s mind-boggling success at reading the room. There have been some furrowed brows, of course—critics who worry that Gerwig has sold out. But for the most part, the movie has won people over. The New York Times’s usually savvy Michelle Goldberg praised the film for taking girls and women seriously. Gerwig “called out the hypocrisy of the manufacturer—Mattel—while getting its blessing on the project. And then, somehow, she—and the company—marketed it all back to us,” Goldberg marveled.

Oh, please. Mattel’s suits knew exactly what they were doing. Richard Dickson may have gulped hard when he saw rough cuts of a manic Will Farrell playing a Mattel head honcho in the movie, but he’s no fool. To disarm progressive critics, your best bet is self-mockery, meta-irony, and so much smart humor that they’ll stay quiet lest they seem like killjoys. The company even mocks its own PR about Barbie’s earthshaking significance. Early on, a deadpan Helen Mirren narrates: “Thanks to Barbie, all problems and equal rights have been solved.” Mattel understood that Gerwig’s ironic affirmation of female grievance, especially when joyously pinked out, will seduce even the most scowling Barbie-haters to the sisterhood. Remember the exuberant feeling of the movie, buy yourself a Barbie pink-mini weekender bag manufactured by the Beis Travel brand, and carry it on your next trip. Ironically, of course.

Toward the end of the movie, America Ferrara, who plays a Mattel secretary, mother to a surly tween, and thus an apparent representative of ordinary twenty-first-century womanhood, rails about the impossible demands made of women under the patriarchy. Barbie is outfitted with so many layers of irony and leavened by so much manic fun, I wondered whether Gerwig was playing with us even in this apparent moment of earnestness. When Barbie travels into the Real World to find her real self, she encounters Will Farrell presiding over an inept, all-male boardroom of yes-men. When Gerwig wrote this scene, she knew that in the real Real World, four out of 11 Mattel board members are women; that the company was co-founded by a woman; and that the movie was directed by Gerwig, a woman, produced by Margot Robbie, a woman, and blessed with a promotion budget that could have made a serious dent in world hunger. Some patriarchy.

None of this changes the fact that the movie is a hoot. “If you love Barbie, this movie is for you. If you hate Barbie, this movie is for you,” the trailer promises. So go ahead and see it if you’re tempted. Just skip the merch.

Comments are closed.