How the Media Manufactured a ‘Genocide’ A data-driven investigation into the way coverage of Israel’s war in Gaza surpasses actual genocides in Darfur, Rwanda, and beyond by Zach Goldberg

https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/media-manufactured-genocide-gaza

Concept creep describes the phenomenon in which morally potent terms expand beyond their original definitions into ever broader applications. As these terms become more diluted, they also become politically weaponized, shifting public perceptions, priorities, and policy.

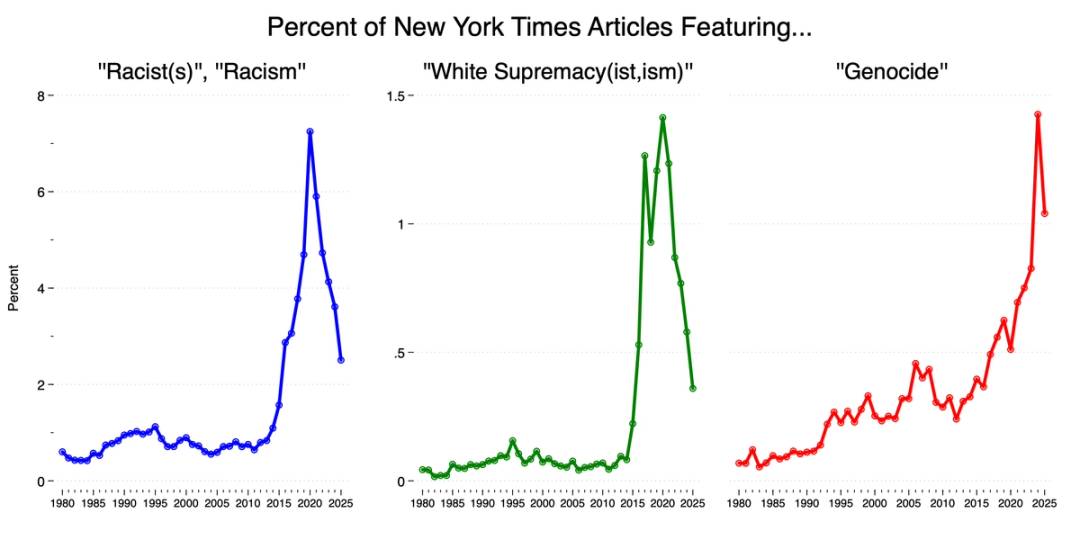

In August 2020, I illustrated in these pages how terms like racism, white supremacy, and privilege saw a dramatic surge in media usage, significantly reshaping public and political perceptions and discourse. The same dynamic, I feared, was beginning to reshape another crucial term: genocide.

Genocide is going the way of racism and white supremacy, I observed on Oct. 19, 2023. Israel hadn’t yet invaded Gaza, but the mainstream media template for response to Hamas’ murderous Oct. 7 attacks was already set. Sure enough, by 2024, mentions of genocide in The New York Times (1.43% of all articles) had eclipsed the paper’s earlier peak for white supremacy (1.41% in 2020) and, though not matching the peak for racism/racist(s) (7.2% in 2020), still reflected a similar pattern of conceptual escalation.

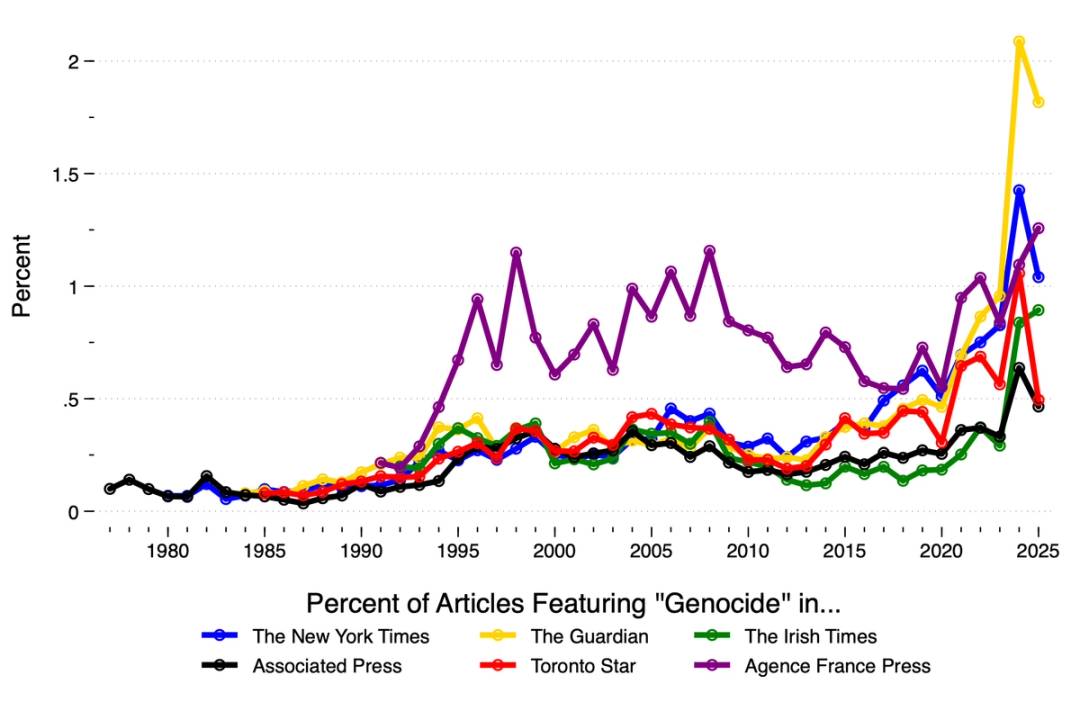

Upon closer examination, however, much like the widespread surge in race-related terminology during the “Great Awokening,” The New York Times was far from alone, as references to genocide reached unprecedented highs across numerous major news outlets, including The Guardian and the Associated Press.

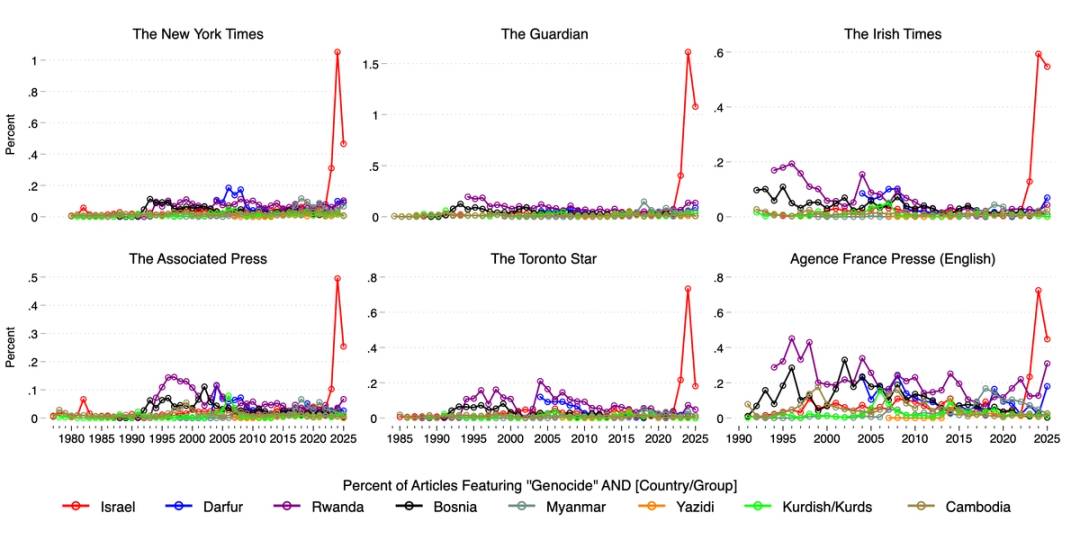

To confirm that these recent spikes were driven primarily by the Israel-Gaza conflict—and to place them in historical context—I analyzed how frequently each of the six outlets paired genocide with countries or groups historically associated with genocide allegations or acts. Using Nexis Uni, I tracked annual coverage associating genocide with well-documented historical cases, including Rwanda (1994), Darfur (2003-2008), Bosnia (1995), Myanmar (2017-present), and the Yazidis (2014-2017).

The results were striking and unambiguous: Coverage linking Israel with genocide has surged far beyond every other agreed-upon historical case of genocide across all examined outlets. In The New York Times, for example, articles pairing Israel and genocide reached levels more than nine times higher than the peak for Rwanda and nearly six times greater than for Darfur. Similarly, in The Guardian, more than 1 percent of all articles now reference both Israel and genocide—a frequency unmatched by any other pairing in recent decades.

This is not a minor anomaly. It marks a profound shift in how the concept of genocide is being applied in public discourse.

If Israel’s war in Gaza qualifies as genocide, it would constitute a striking historical outlier: perhaps the first such case of genocide triggered by a mass terrorist attack involving the slaughter of civilians and the taking of hostages; the first in which the genocider permitted food, fuel, and humanitarian aid to flow into the territory of its purported victims; and potentially the only instance in which the perpetrators lacked any prior plan or ideological commitment to extermination. It may also be unique in that the targeted group’s combatants have deliberately embedded themselves in civilian infrastructure and sought to increase civilian casualties for strategic and propaganda purposes. And it could be the only genocide that might plausibly be halted on the spot—not by the genocider, but by the group claiming victimhood. Specifically, were Hamas to release the hostages and lay down its arms, Israel’s military campaign—having achieved its core objectives—would likely cease.

Yet doing so would mean relinquishing a central propaganda asset: the ability to frame Israel’s actions as a genocidal assault on a defenseless population, a framing that is in turn made possible only by concept creep. Hamas’ casualty figures suggest that far more than half of the dead in Gaza are either Hamas fighters or young men of military age. A ratio of combatants to civilians anywhere close to 1:1 is unrivaled in the history of urban warfare. Does this mean that all past instances of urban warfare—such as U.S. operations in Iraq’s Mosul and Fallujah, let alone Allied bombing attacks on German cities or the Battle of Manila against the Japanese—must retroactively be treated as genocides? Surely, the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki must be considered a genocide, even though historians commonly estimate that the subsequent Imperial Japanese Armed Forces surrender saved at least 2 million lives.

The answers are highly troubling either way. If the new math of genocide is correct, then we have a press teaching a large public that warfare of any kind is always a hideous crime, even when waged in response to murderous attacks by genocidal maniacs and Nazis on defenseless civilians. No means there is to be one rule for Jews and a different rule for everyone else.

Why has the genocide framing of the Gaza conflict dominated media coverage to a far greater extent than conflicts with far clearer claims to that label?

Traditional factors such as access or transparency do not offer satisfactory explanations for the sudden expansion of the term genocide or for the escalation in its use by mainstream outlets. Israel’s open media environment, combined with its geographic proximity to Gaza and the steady stream of imagery and testimony emerging from the territory—often via NGOs and local sources, some affiliated with Hamas—enables consistent and detailed, if often false or misleading, reporting. Far from inoculating Israel against baseless charges, this openness perversely amplifies them, making the country a uniquely visible and morally charged target.

While anti-Israel prejudice in the mainstream media is long-standing and certainly plays a role, framing the problem as one of bias fundamentally misunderstands its nature. The rapid escalation in the use of the term genocide is not the product of ignorance; rather, it is entirely purposeful, with mainstream reporters and essayists engaging in frequent linguistic and legalistic contortions to justify their usage of an inflammatory term in order to delegitimize the actions of one side in a conflict and legitimize the actions of the terrorist organization that started the Gaza war.

In ‘The New York Times,’ articles pairing Israel and genocide reached levels more than nine times higher than the peak for Rwanda and nearly six times greater than for Darfur.

Reporters are willingly serving as the delivery mechanism for targeted information operations—a formerly novel role that U.S. media has adopted on ideological grounds in conflicts at home and abroad over the past decade.

The digitalization of news media is undoubtedly a contributing factor to this new ideologically driven role. As became clear during the rise of Black Lives Matter and the broader Great Awokening, emotionally charged and often graphic content now spreads rapidly across social media—frequently stripped of context or lacking verification—amplifying visceral reactions and shaping siloed public sentiment in real time. In these moments, the role of news media is understood by practitioners not as fact-checking or sense-making, but as amplifying and validating slogans and propaganda lines presented by the virtuous parties. The job of the media is not to separate fact from fiction: Rather, it is to draw halos on the virtuous parties and then mobilize the public on their behalf and against their oppressors.

This dynamic stands in sharp contrast to earlier cases of genocide like Darfur or Rwanda, which unfolded largely in the pre-smartphone, pre-social media era, when the speed, reach, and emotional immediacy of conflict-related imagery were far more limited. In contrast, today’s digital ecosystem, in which traditional media operates symbiotically with social media, places mounting pressure on mainstream outlets to engage and respond, often reinforcing moralized framings that resonate with viral narratives more than with legal precision or empirical balance.

Digital engagement powerfully influences which frame dominates the global discourse, with consequences far beyond rhetoric: shaping historical memory and, most immediately, weaponizing the framing to enact policy targeting Israel, looking to destabilize its government and pressure it to concede to Hamas.

Domestically, the genocide framing solidifies political organization, primarily on the Democratic side, but increasingly in a faction of the right looking to shape Donald Trump’s policy in the Middle East. Consistent with this top-down mobilization, a March 2025 Pew survey found that unfavorable views of Israel among Americans rose sharply over just three years—from 42 percent in 2022 to 53 percent in 2025. The increase was especially pronounced among Democrats, with unfavorable views jumping from 53 to 69 percent, compared to a more modest rise from 27 to 37 percent among Republicans. Gallup data echo this trend: The share of Americans whose sympathies lie more with the Israelis than with the Palestinians fell from 54 percent in 2023 to a record low of 46 percent in 2025. Among Democrats, the drop was steep—from 38 percent siding with Israelis in 2023 to 21 percent in 2025, while support for Palestinians rose to a record 59 percent. Republican attitudes shifted less dramatically, with pro-Israel sympathies dipping slightly from 78 to 75 percent and support for Palestinians hovering around 10 percent.

In short, media coverage does not dictate public opinion, but it helps set the tone and frame the moral stakes. Moreover, similar to the BLM riots, the mainstreaming of the genocide frame provides political top cover for an activist vanguard, such as the pro-Palestinian movement, which began on college campuses and has grown increasingly violent. A similar tactic has emerged among so-called influencers on the right, which similarly has attached itself to the frames of genocide, starvation, and killing Christians, to promote an anti-Israel and even anti-Jewish line. The unprecedented volume of atrocity rhetoric attached to Israel in mainstream outlets is not merely a mirror of preexisting outrage; it is a megaphone, broadcasting the idea that Jews are collectively and unambiguously guilty of the darkest of crimes. It is unsurprising that assertions of collective guilt on the part of “Israelis” and “Zionists” bleed into even broader attitudes toward Jews, resulting most recently in two back-to-back deadly attacks, which took the lives of a young couple and torched an 88-year-old Holocaust survivor.

We need our moral language to retain its clarity and gravity, not to mention its anchoring in legal and historical reality. Once terms like genocide and ethnic cleansing become routine descriptors for controversial wars or asymmetric conflicts, they lose their power to name the world’s most unspeakable crimes. That erosion weakens our ability to recognize and respond to real genocides when they occur—and distorts our understanding of those that already have, while diminishing the agency and true horror of genocidal actions.

Comments are closed.