Attacking Jews at Harvard Doesn’t Just Go Unpunished. It Gets Rewarded.By Johanna Berkman

https://www.thefp.com/p/attacking-jews-at-harvard-doesnt?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Instead of discipline, the students behind an attack that went viral got a fellowship, accolades—and a commencement spotlight.

In the year and a half since the Hamas massacre of October 7, 2023, there have been so many alarming incidents on college campuses aimed at Jews. Many stick out for their grotesque imagery, for their outrageous slanders, and for their Soviet-style tactics. But the incident that I remember most vividly is the one that took place at Harvard University less than two weeks after Hamas invaded Israel, killing 1,200 people and kidnapping 250 more.

No one was physically injured that day. But the fact remained that the incident was wildly beyond the pale: a group of Harvard students surrounding another student, an Israeli named Yoav Segev, repeatedly screaming “Shame!” in his face, blocking his path, and forcing him to leave a part of campus that he was entitled to be in just as much as they were.

Video of the confrontation quickly went viral. You can watch it here.

The incident might have just disappeared from the news, like so many other videos of post-October 7 antisemitism on campus, if not for another shocking fact. The two aggressors who were the easiest to identify, because they were not wearing masks or hoodies and did not have keffiyehs around their faces, were not just Harvard students. They were also Harvard employees.

Ibrahim Bharmal was a Harvard Law School student and an editor at the Harvard Law Review. He was also a law-school teaching fellow in a civil procedure class. Elom Tettey-Tamaklo was a student at Harvard Divinity School. He was also a residential Harvard proctor, someone who advised first-year Harvard College students and lived in their dorm.

In other words, these were not random outside agitators or foolish 18-year-old college students trying to prove their radical clout. They had been chosen by Harvard—Bharmal by its faculty, Tettey-Tamaklo by its administrators—to be leaders, role models, and part of the very fabric of the institution itself.

For those who wanted to simply wave off the outbreak of harassment against Jewish students on elite American college campuses as much ado being done by outsiders, the Harvard video proved otherwise. Yet Harvard’s president at the time, Claudine Gay, said nothing publicly about it until three weeks later.

In an email to the Harvard community, Gay said that Harvard police were investigating and that “consistent with our standard practice, once law enforcement’s inquiry is complete, the University will address the incident through its student disciplinary procedures to determine if University policies or codes of conduct have been violated.”

In recent weeks, Harvard has been trying to argue that it is working hard to address antisemitism on its campus. Three weeks ago, Harvard released its long-overdue report on campus antisemitism. But the report was released on the same day as a separate Harvard report on anti-Muslim, anti-Arab, and anti-Palestinian bias, as if the two problems were of equal measure.

In a letter released with the two reports, Harvard president Alan Garber wrote that Harvard must address the challenges that it faces “with determination at every level of the University by effectively tackling issues that arise when our students congregate. . . and when our policies are violated, ensuring that our disciplinary processes are fair, consistent, and effective.”

Garber also got uncharacteristically personal in an email to the Harvard community. “As a Jew and as an American, I know very well that there are valid concerns about rising antisemitism. To address it effectively requires understanding, intention, and vigilance. Harvard takes that work seriously. We will continue to fight hate with the urgency it demands,” he wrote.

It all sounded good. But what was Harvard actually doing to determine whether any of its policies or codes of conduct had been violated? And how was it holding accountable those responsible for any violations?

The Trump administration, as part of the demands that led to Harvard’s retaliatory lawsuit last month, said that “meaningful discipline” at Harvard “must include permanently expelling the students involved in the October 18 assault.”

An investigation by The Free Press into the October 18 confrontation caught on video and the resulting criminal case reveals that Harvard and its police department played a very significant role in delaying the case and thereby influencing its course and outcome. In doing so, Harvard and its police department, whose chief resigned this month in the wake of a nearly unanimous no-confidence vote against him, worked at cross-purposes with the Suffolk County, Massachusetts, district attorney’s office—and with the pursuit of justice itself.

None of this might even have been an issue if Harvard had dealt with the incident immediately and decisively.

Because the incident at Harvard happened on campus, the Harvard police were in charge of the investigation. That investigation, especially because the evidence was on video, should have been completed within weeks, and the case probably should have taken one to two months at most, according to current and former prosecutors who spoke to The Free Press.

Instead, Suffolk County prosecutors were stymied by a lack of cooperation from the Harvard police, who wouldn’t help them identify three additional people who were shown on video menacing Segev.

Suffolk County assistant district attorney Ursula Knight told the court last fall that there were “additional individuals who had been identified to the Harvard police department. They, of course, were expected to investigate those individuals, but they have essentially refused to do that work, which is, as you might imagine, a surprise to the Commonwealth.” Knight also said that “we have made several requests to them to look into this information. And they have been unwilling to follow up.”

“Harvard had no role in determining the pace, sequence, or outcome of court proceedings pertaining to this matter,” a Harvard spokesperson told The Free Press. The spokesperson also said that Harvard and its police department “cooperated fully with the Suffolk County DA’s investigation into this matter.”

Meanwhile, prosecutors brought in Boston police as part of a last-ditch effort—11 months after the fact—to plow ahead on their own.

Last month, a day before Harvard released its antisemitism report and about 18 months after the video went viral, the case ended with a whimper, not a bang. A judge ordered Bharmal and Tettey-Tamaklo, charged with misdemeanor assault and battery, to perform 80 hours of community service and to complete an in-person anger-management class as part of a pretrial diversion program. They will also take a negotiation class at—where else?—Harvard.

Now, Bharmal and Tettey-Tamaklo are set to graduate next week, at which point Harvard’s ability to take disciplinary action against them will no longer just be controversial. It will be moot. Segev’s lawyers told The Free Press that Garber and other Harvard officials haven’t responded to their questions about whether Harvard has finished a disciplinary process for Bharmal and Tettey-Tamaklo.

Frustrated by the lack of response, Segev’s lawyers sent a letter to Harvard late today, obtained exclusively by The Free Press, accusing it of lying when it stated that, in accordance with its “standard practice,” Bharmal’s and Tettey-Tamaklo’s disciplinary process could only begin once the criminal case was finished.

“Of course, there was never any ‘standard practice’ —it was an effort to delay and obfuscate,” the lawyers wrote. The letter added: “Would Harvard really let students in white hoods, who attacked a Black student, roam around campus the next two years freely, in good standing because of some unwritten practice? Or would it have expelled them immediately?”

In his first interview since the incident, Segev told The Free Press, “I think the biggest issue at Harvard is inconsistent enforcement of rules, and I think the root cause of that is a faculty and staff that are full of ideologues instead of balanced thinkers. The reality is that the faculty, the staff, and the administration are completely broken.”

Before Harvard devolved from being an institution where people of all different backgrounds and beliefs could freely exchange ideas and learn from each other, even if (and perhaps especially if) they did not agree, Ibrahim Bharmal and Elom Tettey-Tamaklo might have met Yoav Segev at a Harvard graduate-school event and been able to talk. Perhaps they might have even discussed their differing political perspectives on the Middle East—which, of the three, only Segev is from—and where his family has lived since the 1800s.

Segev’s parents were Israeli diplomats stationed in Qatar in 1997 when his mother went into labor. “Yoav of Arabia,” said the headline in an Israeli newspaper, which heralded him as the first Israeli to be born in Qatar.

After moving to the U.S. from Israel, Segev grew up in the Boston suburbs and became a U.S. citizen at 16. Amid frequent trips to visit his family in Israel, including a grandmother with shrapnel in her thigh from a long-ago attack, Segev saw himself as destined to help bring about peace in the land of eternal war. “Solving the Middle East conflict dominated our dinner table conversations,” he told The Free Press. “My upbringing emphasized diplomacy and building bridges.”

By the time Segev applied to Harvard Business School, he had a golden résumé to go along with his big ambitions: Oxford, followed by positions at Morgan Stanley, Charlesbank Capital Partners, and Boston Consulting Group, where he worked between Boston and Tel Aviv. But what inspired him most was volunteering at an Israeli nonprofit incubator of start-up companies which have both Arab and Jewish co-founders.

“Once people are working together, it’s hard to hate them. And once people have an economic investment in a place, it’s hard to blow it up,” he said. At Harvard Business School, Segev hoped to leverage the Abraham Accords in order to drive this kind of joint investment at scale.

Hamas attacked Israel just two months after Segev arrived at Harvard. The fact that 33 Harvard student groups quickly signed a joint statement blaming “the Israeli regime” for “all unfolding violence” only deepened his anguish, but he quickly decided to take action. “The university was failing dramatically,” he said. “I was trying to be a leader because there was a vacuum.” And so he spoke to his business school section about his personal background and encouraged them to take positive action.

“While my family fights and cowers, I walk around a manicured campus where even the squirrels are shampooed,” he told his fellow students. “But if I’m here, I’ll fight the way I know how. I’ll educate. I’ll share my story.”

“You have a powerful voice,” Segev added. “You can stand up to antisemitism or you can amplify hate. That choice is yours.” Segev gave a similar talk twice more—at the business school and then at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government—within the next week, including the day before the confrontation.

Bharmal arrived at Harvard Law School in 2021, and Tettey-Tamaklo arrived at Harvard Divinity School in 2022. Bharmal grew up in Orange County, California, the son of Pakistani immigrants. After graduating from Stanford University, he taught English to Arabic speakers at a refugee camp and was an immigration law clerk at the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), an anti-Israel group.

He later told the court that his goal was to become “a grassroots immigration and civil rights lawyer in California and eventually enter local government.”

Tettey-Tamaklo was born in Atlanta and grew up in Ghana. After graduating from Haverford College, he worked as an intern for the UN’s Palestinian refugee agency, known as UNRWA, in Amman, Jordan; a graduate research assistant to UN special rapporteur Francesca Albanese; a college counselor at the Ramallah Friends School in the West Bank; and a conflict-management trainer for the U.S. Institute of Peace.

“Every conversation with Elom is a safe space,” one Harvard proctor wrote about Tettey-Tamaklo in a letter of support filed as part of the court case.

In 2023, Tettey-Tamaklo wrote a blog post for the Beirut-based Institute for Palestine Studies praising Fatima Bernawi, a Palestinian woman who planted a bomb in 1967 at a Jerusalem movie theater screening a film about the Six-Day War. The bomb failed to detonate. Tettey-Tamaklo wrote that Bernawi “nearly carried out an attack on an Israeli establishment frequented by occupation forces (IOF).”

A “true appreciation and celebration of underrepresented histories of Palestinian women like Bernawi—among others—cannot be relegated to the dusty quarters of history,” wrote Tettey-Tamaklo. “They must be celebrated.”

Bharmal, meanwhile, caused friction around campus. In the fall of 2021, he invited everyone in his first-year law section to a party at his apartment. But when a classmate who was a member of the Federalist Society showed up, Bharmal threw him out, according to people familiar with what happened.

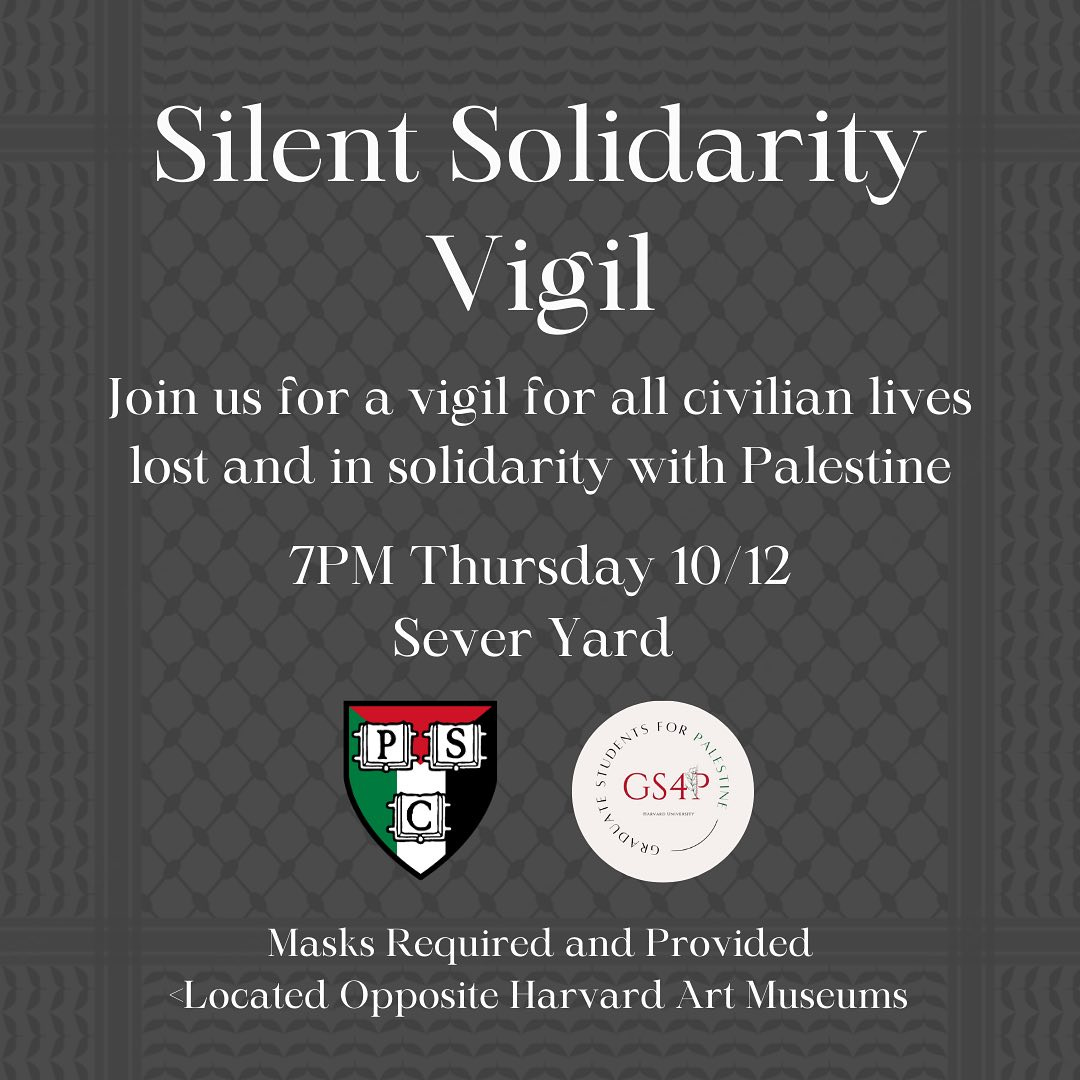

Three days after Hamas attacked Israel, Bharmal sent all 160 students in the civil procedure class for which he was a teaching fellow an email that began: “I hope you’re enjoying the long weekend.” The email included a flyer promoting a “vigil for all civilian lives lost and in solidarity with Palestine.”

A Jewish student who received the email complained to the class’s professor, James Greiner, who responded within minutes. The invitation to the vigil “was sent without my authorization,” Greiner wrote to the class. “I do not endorse that event, nor do I decline to endorse it.” On a campus where loud and proud conformity to progressive values was often the default, Greiner’s statement was a rare public declaration of political neutrality.

Neither Bharmal nor Tettey-Tamaklo responded to requests for comment.

The lives of Yoav Segev, Ibrahim Bharmal, and Elom Tettey-Tamaklo collided during the October 18 “die-in” in front of Klarman Hall on the Harvard Business School campus. Former president Obama was slated to be the keynote speaker at a “Future of the Internet” conference at the business school that afternoon, and protesters were marching there from Harvard Yard, while a news helicopter hovered. “Barry, Barry, you can’t hide,” they chanted, “we charge you with genocide.” They also chanted, “Fuck Harvard Business School.” (Obama canceled at the last minute, citing Covid-like symptoms.)

In front of Klarman, about 100 students were lying in the grass, holding up signs with slogans like “SILENCE IS COMPLICITY” and “LET GAZA LIVE,” while a woman spoke through a loudspeaker: “You can see bodies of children piled up. . . . I tended to a man who had his leg blown off.”

Segev, who lived in a campus apartment nearby, walked through the protest, filming it with his phone. “I’m allowed to be here,” he said when someone wearing a neon green vest approached. “We’re allowed to cover you,” the student replied.

In recent days, there had been controversy at Harvard over pro-Palestine protesters being doxed. There had even been a truck in Harvard Square with a video screen which displayed, under the words “Harvard’s Leading Antisemites,” photographs of Harvard students whose organizations had signed the now infamous anti-Israel statement.The campus was tense.

Soon, several students surrounded Segev, blocking him with their bodies and keffiyehs. Bharmal stood out for having dark hair which was dyed platinum blond on top. Tettey-Tamaklo had dreadlocks.

“Please don’t grab me,” said Segev. “I’m not grabbing anyone. Don’t grab me.” Someone said, “Just let him go. Just let him go.”

There were shouts: “Exit! Exit! Show him the exit!” The group surrounding Segev was growing larger.

“I live here,” Segev said. Protesters shouted in his face, “Shame! Shame! Shame!”

“Let him walk! It’s a public space! He’s a student!” someone shouted. “Don’t touch him! Don’t touch him!”

Protesters lying on the ground soon joined in the taunt. “Shame! Shame! Shame!”

Harvard police stationed nearby came over to Segev once he was inside an academic building. So did a business school administrator who told Segev that he was sorry about what had just happened, adding that Segev could skip the midterm exam that he was soon to take.

Segev chose to take the exam, but he walked there through tunnels beneath the business school to avoid the protesters.

By the time he got out of his exam two hours later, video of the incident was already online. The viral storm was brewing.

Segev met with Harvard police officers and filed a formal complaint. The university, however, took no public action or even made a statement.

Five days after the confrontation, Senator Mitt Romney and several fellow Harvard Business School alumni, including Seth Klarman, the namesake donor of Klarman Hall, wrote an open letter to Harvard. “This is not leadership,” the letter said. “Leaders should state that the campus police are viewing all videos of these hate-filled, violent altercations and that any students, faculty members or employees who have violated the code of conduct will be suspended or expelled.”

A little more than two weeks later, Gay sent out a long email about antisemitism in which she briefly stated how and when the university would address what had happened in front of Klarman Hall. But she made no condemnation, simply writing, “I have heard from many community members about the incident.”

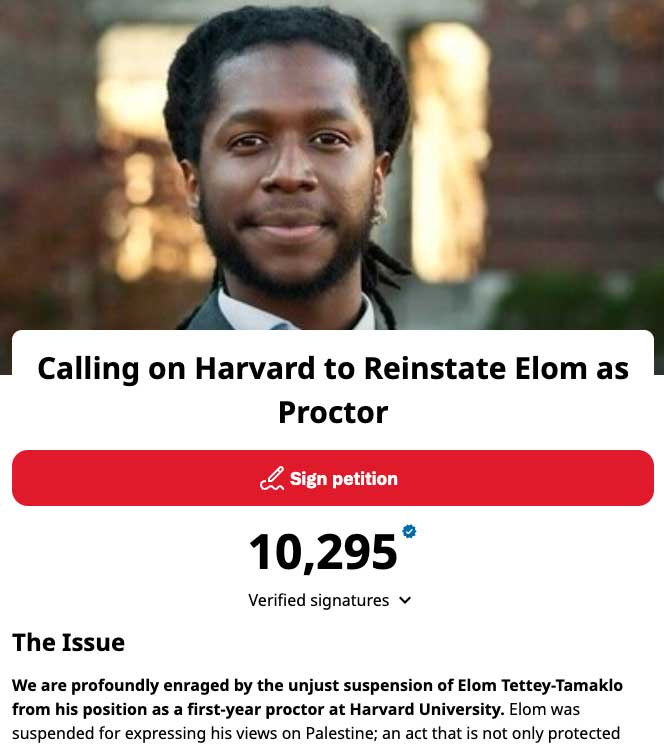

The next day, Tettey-Tamaklo was removed from his duties as proctor and moved out of his Harvard Yard dormitory. In response, Harvard’s Faculty and Staff for Justice in Palestine said it felt “growing dismay with a climate on campus that has diverged from the university’s stated commitment to foster an environment ‘that values the dignity of each person and provides an environment in which everyone can thrive.’ ”

More than 10,000 people signed a petition titled “Calling on Harvard to Reinstate Elom as Proctor.” A “Bring Back Our Proctor” post on Medium said Harvard “should have centered the opinions of those who interacted with him the most: his proctees.” Tettey-Tamaklo’s suspension “re-emphasizes the truth about Harvard’s values,” the post added. “Harvard’s prioritization of economic capital is reflective of its complicity in Israeli apartheid.”

The post also described Segev as “an individual unaffiliated with the action” who “aggressively started stepping over students and recording us.” Tettey-Tamaklo, by contrast, was described as a “tireless defendant of justice” who “fights for all to live freely and openly on this campus” and is known for “his kindness, compassion, and tireless conviction for good.”

Bharmal told Harvard Law School administrators that he had been a safety marshal at the protest. “Halfway through the protest,” he wrote in an email, “an unidentified counter-protester weaved through the crowd in order to record students’ faces up close. Along with multiple other safety marshals, I stepped in to try to block his invasive recording with a scarf. At no point did I make purposeful contact with him. My intention was to de-escalate.”

Segev met with the police once more, and then, he said, “everything stopped. We were filing complaints with Harvard, and nobody was getting back to us. We had no idea what was going on.”

A few months later, Tettey-Tamaklo read a poem during an online event called “Lessons from Liberation Theology in Times of Genocide,” sponsored by the Kairos Center for Religions, Rights, and Social Justice.

“At the end of history there shall be no pardon left for you, you brood of vipers, you who siphon the lifeblood of the innocent and intoxicate yourselves with it. You dangerous death doulas who curse God by dishonoring humanity…May your blood be viscous as theirs, and may your faith resemble theirs…Weep for yourselves, for God has closed his ears towards your wicked souls.”

In December 2023, Gay fumbled through a congressional hearing about antisemitism when asked by Representative Elise Stefanik if calling for the genocide of the Jews violated Harvard’s policies. Gay responded that it depended on the “context.” Meanwhile, Representative Lisa McClain, of Michigan, did her best to pin Gay down on another topic: discipline for those involved in the incident at Harvard Business School.

“What action was taken from Harvard when a Jewish student was mobbed on your campus last month?” McClain asked. “Action, not lip service, action, ma’am?”

“So,” began Gay, “as you may know, that is an incident that is currently under investigation by [the Harvard police department] and the FBI.

“Okay, any action?” retorted McClain.

Gay continued, “And when that —”

“I’m looking for the action,” said McClain.

“And when that investigation is complete,” Gay continued, “we will address it through a student disciplinary.” She resigned as president less than a month later.

The day after Gay quit, an outside lawyer for Harvard, Katya Jestin, reached out to the lawyers representing Segev. Segev had been told that Harvard couldn’t move forward with his complaints against Bharmal and Tettey-Tamaklo at their respective graduate schools if Segev’s identity in the complaints remained anonymous. He decided not to proceed, concerned that doing so would only attract more harassment.

That decision didn’t let Harvard off the hook, however, according to Doug Brooks, one of Segev’s lawyers. “We had made the point to Harvard that just because you’re saying your disciplinary process doesn’t allow for anonymity, you still have a Title VI obligation to protect your Jewish students,” said Brooks, referring to a federal law that prohibits recipients of federal aid from discrimination based on race, color, and national origin.

Brooks said that he was told by Harvard’s lawyer that it was starting a different process that would be an “internal investigation” of the incident. In April 2024, Brooks and Segev met with Jestin and another lawyer for Harvard for more than two hours in a conference room at Harvard Business School.

“It was very upsetting,” said Segev, describing a process in which Harvard’s lawyers played video of the incident on a big television screen, pausing the video every few seconds to ask him what he had been experiencing in each frame.

When Brooks contacted Jestin the next month by email, asking when the investigation might be completed, Jestin told him that she couldn’t comment. She had the same reply when he asked again nine months later. “Why would Harvard start an investigation and then stop it?” Brooks asked. “Who does that?”

In May 2024, Bharmal and Tettey-Tamaklo were charged with assault and battery, and a civil rights violation. (The latter charge was ultimately dismissed.) Why had it taken so long? Part of the answer is that a Harvard police sergeant believed that three other people shown in video of the incident should also face the same charges.

Those people were identified as “unknown person #1,” “unknown person #2,” and “unknown person #3,” according to an incident report filed by Harvard University police sergeant Thomas Karns. Determined to identify them, the Suffolk County district attorney’s office kept asking Harvard police to interview more witnesses and possible suspects, but the work wasn’t getting done. This back-and-forth delayed the arraignment of Bharmal and Tettey-Tamaklo.

Last summer, Harvard police commander Meghan Caine told Ursula Knight, the assistant district attorney in charge of the prosecutions, that the Harvard police department would not continue to investigate the case without a subpoena.

The upshot of Harvard’s message was: If you want to bring charges, bring charges. We won’t investigate further.

Harvard’s commencement is now just eight days away. Instead of being expelled, or even suspended, Bharmal and Tettey-Tamaklo will graduate with honors and accolades. Tettey-Tamaklo has been voted a class marshal by his divinity school classmates. He will help lead them into Harvard Yard.

Bharmal recently won a $65,000 public-interest law fellowship from Harvard Law Review to go back to work at CAIR. Harvard Law School’s admissions office then featured Bharmal and another student in a blog post about how their dual degrees “empowered them to challenge established legal systems and advocate for systemic solutions, creating lasting change for communities.”

“Because everything is decentralized, and individuals and units have so much autonomy, people feel free to do things that can create huge headaches for the Harvard president,” said Harvard Law School professor Jesse Fried. “They either don’t think about the impact or don’t care. I keep thinking of the Chinese proverb: ‘The mountains are high, and the emperor is far away.’ ”

Segev, meanwhile, is looking forward to receiving his MBA and working on a new investment fund he is setting up. Despite all that has happened, he is still hopeful that Harvard might soon begin to rectify how it treats Jewish and Israeli students.

“I think the world and America are a better place when Harvard is strong,” Segev told me. “But Harvard is currently a diseased institution which is filled with ideologues instead of researchers and top-level thinkers who are committed to the pursuit of truth and world-advancing ideas. A symptom of the disease is a pervasive culture of antisemitism. I’m not trying to tear the place down,” he said. “I’m trying to help fix it.”

Comments are closed.