How Qatar Bought America The tiny Gulf nation has spent almost $100 billion to establish its influence in Congress, universities, newsrooms, think tanks, and corporations. What does it want in return?By Frannie Block and Jay Solomon

https://www.thefp.com/p/how-qatar-bought-america

On Wednesday, Donald Trump will travel to Qatar. On his trip, the president will visit Al Udeid Air Base, the largest American military facility in the region, and attend meetings with the ruling Al Thani family. Perhaps he will also thank them for the $400 million gift of a luxury Boeing 747-8 jumbo jet that will reportedly be retrofitted for his use, and then transferred to his presidential library.

The airplane deal was signed off by Attorney General Pam Bondi. She used to work at a Washington, D.C., lobbying firm that received $115,000 a month from Qatar to fight human trafficking, according to a 2019 contract reviewed by The Free Press.

She’s not the only one in the administration with ties to the Persian Gulf state.

President Trump’s chief of staff, Susie Wiles, led lobbying firm Mercury Public Affairs when it represented Qatar’s embassy in Washington. FBI Director Kash Patel worked as a consultant for Qatar, though he didn’t register as a foreign agent.

And then there is Steve Witkoff, president Trump’s longtime friend and senior adviser, who is accompanying him on his trip this week. For months now, Witkoff has served as Trump’s special envoy to the Middle East—and his name has been floated as a future national security adviser. Witkoff also happens to be a beneficiary of Qatar’s largesse: In 2023, Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund bought out his faltering investment in New York’s Park Lane Hotel for $623 million.

Meanwhile, the Trump Organization is hard at work planning a new luxury golf resort near Qatar’s capital, Doha, in partnership with a Qatari company. Trump’s son Donald Trump Jr. will speak next week at the invitation-only Qatar Economic Forum in a session titled “Investing in America.”

If you were just a casual reader of these facts—an ordinary American who doesn’t think much about the Middle East after America’s traumatic wars of the 2000s—you would think Qatar is a top American ally, a trustworthy partner, and a key hub of international commerce—a country in good enough standing that the president of the United States would use its plane as Air Force One.

But Qatar is also a seat of the Muslim Brotherhood, a crucial source of financing to Hamas, a diplomatic and energy partner of Iran, a refuge for the Taliban’s exiled political leadership, financier and cheerleader of Palestinian terrorism, and the chief propagandist of Islamism through its media powerhouse, Al Jazeera, which reaches 430 million people in more than 150 countries.

Key members of Qatar’s royal family have made their admiration for Islamism—and Hamas specifically—very clear. Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, the mother of Qatar’s emir and the chairperson of an educational nonprofit funneling millions into American schools, praised the mastermind of the October 7, 2023 massacre, Yahya Sinwar: “He will live on,” she wrote on X after his death last year, “and they will be gone.”

The question is: How did a refuge of Islamist radicalism, a country criticized for modern-day slave labor, become the center of global politics and commerce? How did this tiny peninsular country of 300,000 citizens and millions of noncitizen migrant workers manage to put itself smack-dab in the center of global diplomacy—and so successfully ingratiate itself within the Trump administration?

Over the past few months, The Free Press investigated these questions. What we found is that no obstacle, no history, no bad headline is too big for Qatar’s money.

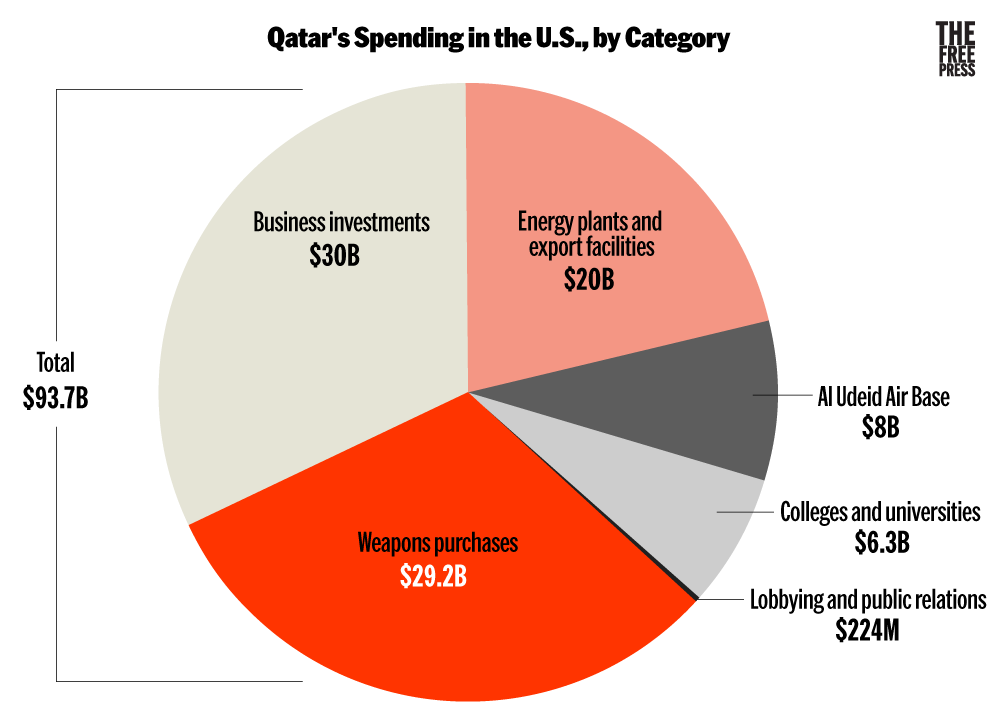

Qatar has spent almost $100 billion to establish its legitimacy in Congress, American colleges and universities, U.S. newsrooms, think tanks, and corporations. Over the past two decades, it has poured those billions into purchases of American-made weapons and business investments ranging from U.S. real estate to energy plants. It built—and still pays for—the Al Udeid Air Base, even as the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have ended. Doha finances research and campuses at prestigious American universities. And its lobbyists have the connections needed to open all the right doors in Washington. Since 2017, it has spent $225 million on lobbying and public-relations efforts in the nation’s capital.

The Free Press reviewed thousands of lobbying, real estate, and corporate filings. We interviewed dozens of American, European, and Middle Eastern diplomats and defense officials. We also analyzed secret intelligence briefings and previously undisclosed government documents. Together, they explain how Qatar has amassed so many loyal allies in America.

We sought comment from Qatar’s government numerous times, including from its embassy in Washington, which serves as Doha’s primary emissary in the U.S., as well as from PR officials and lobbyists whose firms represent or represented Qatar. Those efforts included detailed questions and the conclusions of this investigation. The Free Press never received a response.

Countries have always used money to advance their interests abroad, and recipients know that the bargain often includes realpolitik that requires them to hold their noses. Qatar is an extreme example of that geopolitical codependence.

The influence built by Qatar in the U.S. has no modern parallel, The Free Press found, whether compared with large American companies seeking to influence antitrust policy, energy firms trying to win new drilling rights, or other foreign governments aiming to shape U.S. policy—or shield themselves from it. For comparison, Qatar spent three times more in the U.S. than Israel did on lobbyists, public-relations advisers, and other foreign agents in 2021—and nearly two-thirds as much as China did, according to the government’s latest reports.

In President Trump and his friends and family, Qatar seems to have found a political leader and business partner who is unconcerned about keeping private and public interests separate.

The golf club and luxury villas deal announced by the Trump Organization last month appears to skirt a promise the company made to refrain from any business dealings with foreign governments during the president’s second term. The Air Force One deal also appears to violate the Emoluments Clause of the Constitution.

“I think it’s a great gesture from Qatar. I appreciate it very much,” the president said about the Qatari jet, dubbed the “palace in the sky.” He suggested that only “a stupid person” would turn down the offer of “a free, very expensive airplane.”

But of course, nothing is free. What Qatar hopes to achieve through its profligate strategy in Washington is nothing short of a remaking of the global order that secures America’s fidelity to Doha over other Gulf powers, namely Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, while neutering the U.S.’s ability to respond to Islamist threats and making our political class willing to overlook them. This compromises the ability of America’s political class to—as Saudi Arabia’s former foreign minister, Adel al-Jubeir, put it in 2018—understand that “the Qataris harbor and shelter terrorists. . . . The Qataris use their media platforms to spread hate.”

Host to the Muslim Brotherhood—and a U.S. Air Base

The U.S.’s entanglement with the Arab world began in the early 1800s with American naval battles against the Barbary pirates off the coast of North Africa. The Al Thani family, which now rules Qatar, was just a minor tribe over most of the past two centuries, dwarfed by the Al Saud family in modern-day Saudi Arabia, the Al Khalifa clan in today’s Bahrain, and the Al Nahyan family in Abu Dhabi.

As recently as the 1980s, diplomats and businessmen described Doha as a barren place with stifling heat. The economy was fueled largely by pearl farming. The Al Thanis promoted a conservative brand of Islam that left its women covered and the country largely dry of alcohol. From a distance, the only discernible building on Doha’s waterfront promenade was the pyramid-shaped Sheraton hotel.

“I mean, sleepy doesn’t really do it justice,” Sir John Jenkins, a former British diplomat focused on the Middle East, told The Free Press about his visits then. “There was nothing going on.”

Qatar’s economic fortunes soared when American and European energy giants, such as ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips, developed the technology to exploit what turned out to be one of the largest natural gas reserves in the world. Qatar began exporting liquefied natural gas to Asia in 1997. Per-capita gross domestic product is now $121,610, among the highest in the world, compared with $89,110 in the U.S., according to the International Monetary Fund.

Money gave the Al Thanis an opportunity to follow the same playbook long used by Persian Gulf rulers: seeking a foreign patron to guarantee their security. Instead of the Ottoman Empire and Great Britain, Qatar turned toward Washington.

In the early 2000s, Qatar successfully wooed the U.S. away from the air base in Saudi Arabia, where it had been for more than a decade after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990. Qatar poured more than $1 billion into the runways, barracks, and hangars of Al Udeid. The facility can house thousands of American troops and is also a regional base for the UK’s Royal Air Force.

Of all of Qatar’s investments in the U.S., Al Udeid is widely agreed to be the shrewdest and most impactful. Steve Witkoff said this March that the Qataris “pay for every dollar of it,” more than $8 billion since 2013. As a result, Qatar has become an indispensable part of the U.S. national security system. Al Udeid is the Pentagon’s primary logistical hub in the Middle East—and the launch point for many U.S. military strikes in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere.

It was a brilliant move for a country looking to shield itself from its far more powerful neighbors. These include Qatar’s Sunni rivals in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and Iran’s revolutionary Shi’ite clerics. Qatar and Iran share a massive offshore gas field, giving Qatar another incentive to align with Washington. And the air base bought Qatar critical protection.

Qatar’s massive subsidies of the air base have also helped win the Al Thanis praise from the Pentagon to Congress to the White House. “You’ve been a great ally, and you’ve helped us with a magnificent military installation and military airport, the likes of which people haven’t seen in a long while,” President Trump told the Emir of Qatar at a dinner at the Treasury Department in 2019.

In 2022, President Biden declared Qatar a “major non-NATO ally” of the U.S., easing the way for more arms sales and greater U.S. military support. Last year, the two countries agreed to extend the lease on Al Udeid for another decade and discussed the possibility of joint-weapons production. “They’ve been an extraordinary partner to us, and Al Udeid Air Base remains a critical juncture for us in the Middle East,” said retired U.S. Army General Joseph Votel, who led the U.S. Central Command in the region from 2016 to 2019.

American diplomats have also expressed gratitude to Qatar for serving as a middleman between the U.S. and adversaries such as Iran, the Taliban in Afghanistan, and Tehran’s proxies, Hamas and Hezbollah. That role has proven especially important during negotiations to release Israeli and American hostages seized by Hamas in 2023 and imprisoned in the Gaza Strip. In March, Steve Witkoff described Qatar’s leaders as “people who don’t have the old sensibilities, people who want to do business.”

But the intertwined relationship is also a source of growing concern among some current and former officials in the U.S. and Europe. They worry that, especially through the air base, the Al Thanis have far too much influence over Pentagon military strategy and operations at a time when a U.S. or Israeli conflict with Iran is a growing possibility, including potential strikes on Tehran’s nuclear sites. Indeed, maintaining the air base in Qatar comes with a significant string attached: The Gulf monarchy has said it would oppose military strikes on Iran from its soil.

Bruce Hoffman, a Georgetown University professor who has studied terrorism and insurgency for almost 50 years, publicly denounced Qatar’s long history of financing Hamas after it massacred 1,200 Israelis and kidnapped 250 more on October 7, 2023.

Hoffman told The Free Press that he soon heard from a “former very senior official” at the Defense Department, who offered some feedback from inside the Pentagon. “That comment wasn’t appreciated about Qatar, because we can’t do anything that endangers the air base,” Hoffman said he was told.

“Qatar has it both ways. They play both sides of the fence,” Hoffman said to The Free Press.

“I can’t think of a single dispute or conflict in the Middle East or Afghanistan that the Qataris made better,” said Jenkins, the former British diplomat. He cited the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan, despite years of mediation, by Doha’s support of Islamist militias and political parties in Syria, Libya, and Egypt.

Most troubling to Qatar’s critics is its deep, abiding relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood, which was born in Egypt in the 1920s and later inspired militant organizations like al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and Hamas. A crackdown in the 1950s led to the migration of many Muslim Brotherhood leaders to the Persian Gulf states, including Qatar.

The Al Thanis welcomed them. Yusuf al-Qaradawi, widely seen as the Muslim Brotherhood’s most important spiritual and religious leader until his 2022 death, hosted a talk show titled Sharia and Life on the government-owned Al Jazeera broadcasting network. His religious edicts justified suicide bombings, condemned homosexuality, and rallied Muslims to fight occupying U.S. forces in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“Martyrdom is a heroic act of choosing to suffer death in the cause of Allah, and that’s why it’s considered by most Muslim scholars as one of the greatest forms of jihad,” Qaradawi declared. In 2017, he was designated a terrorist by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt, but not by Qatar.

That year, the same four countries also imposed a trade and travel embargo on Qatar, demanding that it sever all ties with the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist groups. They told Qatar to stop its global television channel, Al Jazeera, from airing content that they saw as a threat to their stability.

The crisis eventually faded, partly through U.S. mediation. But Qatar continues to be an Islamist safe haven and to fund Al Jazeera, which aired in January a documentary titled What Is Hidden Is Greater. The film featured exclusive, embedded footage of Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, as he evaded Israeli troops in the Gaza Strip. It also documented top military official Mohammed Deif planning attacks on Israeli targets alongside other Hamas terrorists.

“Why would you welcome into your country these forces that could be potentially destabilizing?” asked Steven Cook, a Middle East expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, about whether the haven Qatar provides to extremists is purely politics or a sign of religious devotion. “That’s where I go back and forth. And I think: ‘Well, maybe they are true believers.’ ”

What’s beyond dispute is that Qatar’s support of the Muslim Brotherhood projects its power across the Muslim world from Jordan to Indonesia. “The Qataris are using Islamism as a form of political leverage,” said Magnus Ranstorp, a longtime expert on Islamic movements and terrorism and a strategic adviser at the Swedish Defense University.

Stolen Emails and Smear Tactics

In June 2017, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and other Arab states launched a formal economic siege of Qatar, accusing the country of supporting terrorism and extremism and threatening the stability of their regimes. They demanded that Doha end its support for the Muslim Brotherhood and Al Jazeera. The Al Thanis saw the siege as an existential threat to their rule, Qatari officials have said.

The operation included attempts to sever Doha’s external sea and air routes, and there were rumblings of a Saudi cross-border ground invasion. Qatari nationals also worried about food shortages, necessitating emergency supplies from Iran at one point. As a result, Qatari royals and leaders flocked to Washington to demand that the first Trump administration intervene and negotiate an end to the conflict.

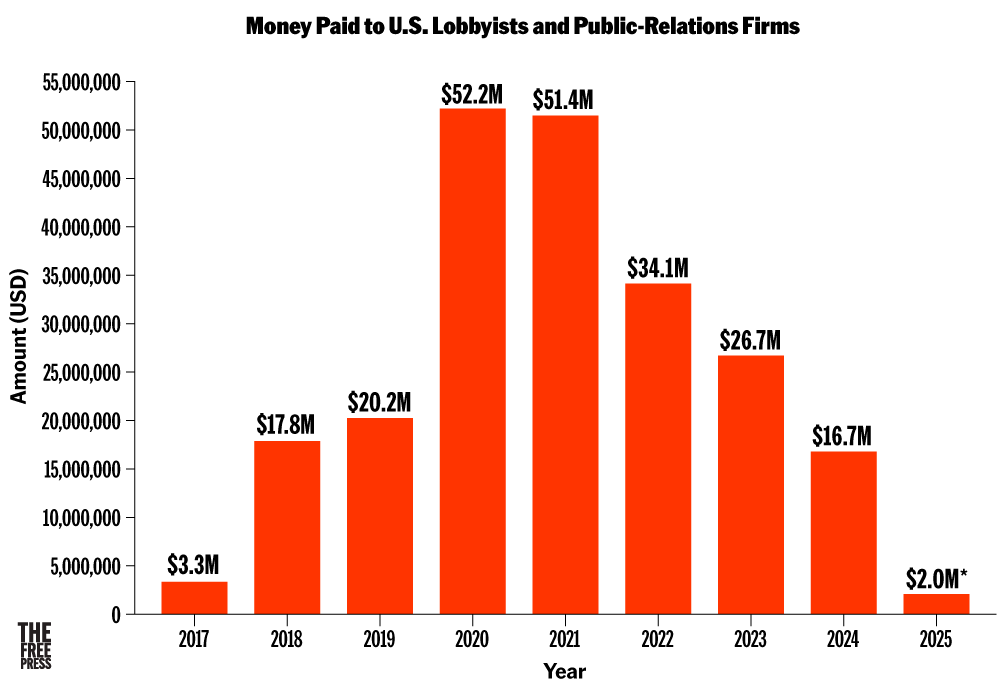

The Al Thanis also initiated one of the most aggressive lobbying and influence operations ever targeted on Washington. This transformed Qatar from a minor meddler in U.S. politics and public policy into a powerhouse that is both courted and feared.

Every foreign government employs lobbyists in the U.S. What is extraordinary about Qatar is its number of lobbyists, how much they’re paid, and their ability to operate within both political parties and across so much of elite Washington.

The U.S. government found that in 2021 alone, Qatar employed 35 registered lobbyists and public-relations firms at a total cost of more than $51 million. In comparison, the total expenditures for the UAE were $35 million. For Saudi Arabia, they were $25 million. The government hasn’t released newer totals.

To get a more complete picture, The Free Press sifted through every filing it could find since the start of 2017 by lobbyists and public-relations firms that reported being paid by Qatar. The Free Press calculated that Qatar has spent $225 million since then, or an average of more than $25 million a year.

Lawyers who specialize in foreign lobbying told The Free Press that these numbers are just part of the picture. Governments aren’t required to tell the Justice Department how much they spend on things like think tanks or hosting U.S. political and congressional delegations. In 2018, The Wall Street Journal reported that Qatar targeted a list of 250 people close to Trump aimed at “getting into his head as much as possible,” in the words of a lobbyist involved in the effort.

One of Qatar’s most loyal allies in the U.S. is former congressman Jim Moran. In his 24 years on Capitol Hill, the Democrat from Virginia played an important role in foreign affairs. He protested against the Sudanese government, opposed the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, and stood out for criticizing what he called the corrupting power of the pro-Israel lobby, especially the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC).

In 2017, Moran was the headliner at a National Press Club event titled “Fighting the Israel Lobby in Congress.” He and a fellow former congressman claimed Israel had the power to block the creation of an independent Palestinian state, undermine Lebanese sovereignty, and run out members of Congress who didn’t bow to Israel’s will. Most provocatively, Moran also said that AIPAC and Jewish Americans were critical players behind the George W. Bush administration’s decision to invade Iraq.

“If the leaders of the Jewish community—particularly the pro-Israeli community—had a different attitude and were willing to get more engaged against the war, I don’t think we’d have a war,” Moran said.

A few months later, Moran signed on as one of Qatar’s lobbyists in Washington.

In coordination with other Qatari-paid lobbyists aligned with Republicans and Democrats, Moran began to promote a network of nongovernmental organizations and think tanks in support of Qatar’s positions on international affairs. Those institutions were often sharply critical of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Israel.

Public records show that Qatar also funded prominent, Washington-based think tanks to the tune of at least $9 million from 2019 to 2023. They included the Brookings Institution ($6 million), the Stimson Center ($2.3 million), RAND ($300,000), and the Middle East Institute ($380,000). In comparison, the UAE has spent $16.7 million on think tanks, while Saudi Arabia has spent more than $2.1 million.

After the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023, Moran met in person with dozens of Democratic and Republican politicians on Capitol Hill to discuss “Qatar’s role as U.S. ally in the Middle East” and the country’s position “vis-à-vis [the] Middle East Conflict,” his lobbying records show. The big names included Maryland senator Chris Van Hollen and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries.

A week after meeting with Jeffries, Moran donated $2,000 to a political action committee supporting Jeffries’ reelection campaign, according to a filing by Moran. Moran’s consulting firm and an outside contractor were paid $400,000 by the Embassy of Qatar for six months of work.

A person familiar with Van Hollen’s work in Congress said he has met with numerous countries, from Qatar to Israel, to learn more about their efforts to free the hostages and end the war.

Also in 2023, as the House neared a vote to possibly end the Biden administration’s use of Qatar to move unfrozen Iranian funds, Moran met with Minnesota Rep. Betty McCollum on the same day that he donated $500 to her campaign. (She voted against the bill, but it passed the House anyway.) In 2024, Moran met with McCollum again to discuss “Qatar’s constructive role in the Gaza conflict,” and he donated $1,000 to her campaign three days later.

McCollum told The Free Press that Moran “works with my office on critical defense innovation issues to improve and advance U.S. national security.” “I always put U.S. national security first,” she said. She also called Qatar “an important U.S. ally in the Middle East.”

Moran played a central role in helping Qatar acquire a marquee location for its new embassy in Washington. Qatar wanted to buy the Beaux Arts–inspired Carnegie Institution for Science’s building, over 120 years old and near the White House, but it wasn’t for sale. Moran told Washingtonian magazine that he and other people close to Qatar called Carnegie board members “at night” to encourage a sale.

Carnegie sold for $65 million, nearly triple the building’s assessed value, despite opposition from Carnegie employees who called Qatar an “oppressive, brutal, and misogynistic regime.”

In some of Qatar’s political dealings, its allies or beneficiaries crossed the line.

Retired U.S. Marine Corps General John Allen and former U.S. ambassador to Pakistan Richard G. Olson Jr., received gifts and consulting contracts from Qatar. In 2017, both men flew to Doha and back, then spoke with Trump administration officials on behalf of Qatar. Neither disclosed being paid for their work.

Olson eventually pleaded guilty to violating federal lobbying and ethics laws. Allen denied lobbying and was never charged. But he resigned from his position as president of the Brookings Institution in 2022.

Last year, prominent Republican lobbyists Barry Bennett and Douglas Watts admitted to failing to register as lobbyists for Qatar. Prosecutors said Bennett’s firm “covertly operated” an organization called Yemen Crisis Watch to highlight alleged war crimes committed by Saudi Arabia and the UAE in Yemen. Qatar paid the two men $2.1 million for their first three months of work. Last year, they reached deferred prosecution agreements with the government to resolve the investigation.

Qatar also hired a consultant who hatched an audacious strategy to neutralize Qatar’s perceived political enemies in Washington that included smearing them.

Early in the first Trump administration, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE were competing for influence, and Qatar seemed to be on the defensive as a result of the 2017 siege. Republican members of Congress were seeking to designate the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization. That’s when a former CIA operative named Kevin Chalker approached Qatar with a plan.

Chalker and his private intelligence company, Global Risk Advisors, drafted a 12-page proposal titled “Project ENDGAME.” It was addressed to the “Qatar Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy” and the “Office of the Secretary General.” A copy of the proposal was reviewed by The Free Press. (You can read it here.)

“Endgame” was a code name for Yousef Al Otaiba, the UAE’s ambassador to the U.S., according to people briefed on the operation. “ENDGAME is the most powerful Ambassador in the U.S. He has allies and assets across Washington, D.C., ready to do his bidding,” the proposal said. “Qatar must act immediately because ENDGAME has infiltrated Trump’s inner circle.”

Chalker’s outfit warned that Qatar’s support for Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood was being used to undermine the Al Thanis. “An attack on Hamas is an attack on Qatar. An attack on the Muslim Brotherhood is an attack on Qatar,” the proposal said.

The proposal named four targets that might be interested in publishing articles based on Otaiba’s private information: The New York Times, The Intercept, Middle East Eye, and the editor of The Grayzone. “Many news organizations won’t publish ENDGAME content, so Qatar’s media assets must play a critical role,” it said.

Soon, some of the UAE ambassador’s emails began popping up on websites and in embarrassing news coverage. He had obviously been hacked.

“Hacked Emails Show Top UAE Diplomat Coordinating with Pro-Israel Think Tank Against Iran,” blared a headline in The Intercept in 2017. A follow-up article was titled “Diplomatic Underground: The Sordid Double Life of Washington’s Most Powerful Ambassador.”

Otaiba declined to comment to The Free Press. Lawyers for Chalker and Global Risk Advisors denied participating in any illegal activity on behalf of Qatar. The government of Qatar has also denied any role in hacking.

The stolen emails spread panic across Washington. One person who worked at a think tank told The Free Press that his bosses sought all of his emails to or from known hacking targets so that it could hunt for any that might be embarrassing.

“Qatar has never faced a threat this dangerous,” the Project ENDGAME proposal said. Now everyone knew how far Qatar would go to fight back.

Flipping Qatar’s Critics

You couldn’t find a louder voice against Qatar in Washington over the past decade than Elliott Broidy. After raising money for Donald Trump’s first presidential campaign and inauguration, Broidy, a Republican political operative, used his connections to try to expose the fossil fuel–rich country’s bloody ties to Hamas, the Muslim Brotherhood, and other Islamist groups.

He helped pay for conferences at prestigious think tanks such as the Hudson Institute and Foundation for Defense of Democracies, where Qatar was denounced in 2017 as a “welcome mat” and a “safe haven” for extremists. He solicited anti-Qatar opinion articles from prominent American diplomats and scholars. He leaned on his personal relationship with Trump to push the White House to back regional rivals Saudi Arabia and the UAE in their diplomatic and economic standoff with Qatar.

Most explosively, Broidy accused Qatar in a lawsuit in 2018 of engineering a computer hack of his devices. This eventually exposed his payoff to a former Playboy model who said he impregnated her, his work as a lobbyist for a Malaysian tycoon ensnared in a giant investment scandal, and his efforts to win a pardon from Trump for a convicted tax cheat.

“Elliott was sort of a one-man show focused on Qatar,” someone who worked with Broidy told The Free Press.

Instead of hiding from those humiliating headlines, Broidy spent tens of millions of dollars on lawyers and a team of public-relations and crisis-communications specialists, who doubled down on making Qatar look bad. In 2023, one of the Qatari lobbyists he sued admitted knowing about the hack and handed over incriminating emails. A judge demanded that he provide even more. It looked like Broidy might win his revenge.

Then he went completely quiet.

After secret talks in Qatar and Europe that included Broidy and senior aides to Qatar’s ruling Al Thani family, he agreed last year to a settlement that paid him more than $150 million, according to people intimately familiar with the deal. He also agreed to abandon his legal fight and any funding of efforts aimed at tarnishing Qatar. Representatives for Broidy declined to comment to The Free Press.

And Broidy is far from the only such story.

During his two decades in the Senate, South Carolina’s Lindsey Graham has made a name for himself as one of Capitol Hill’s staunchest hawks—a champion of U.S. military interventions in the Middle East, a defender of the American-Israel alliance, and a fierce critic of radical Islam.

So when Graham took to the stage at the Sheraton Grand Doha Resort in December 2023, just two months after Hamas’s invasion of Israel, the audience at the Doha Forum might have expected him to drop the hammer on the Al Thani family.

That day, though, Graham showed nothing but admiration and respect. “I want to thank you for what you’ve done for my country,” Graham said. “You get some criticism. Hamas is here. But I know why they’re here. They’re here so they can be talked to. You do things for the world that sometimes are not so popular. But I just want you to know that I appreciate what you do.”

Graham’s praise for Qatar didn’t happen in a vacuum.

Back in 2018, when Graham was known more for his vigorous support of the Iraq War and friendship with John McCain, the late Arizona senator, Qatar began investing hundreds of millions of dollars into Graham’s home state of South Carolina.

This came mostly through Qatar Airways’ purchase of 40 Boeing aircraft, including 787 Dreamliners made near Charleston that were part of an $11.7 billion order in 2016. Qatari-owned military technology company Barzan Aeronautical then announced plans to build spy drones at a new facility nearby.

Graham and South Carolina governor Henry McMaster also met with leaders of Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund to discuss additional investments in the state. Charleston and Doha became “sister cities,” and Qatar’s embassy donated $100,000 to Charleston for Covid relief aid. (It’s not just South Carolina: Qatar said it has invested more than $21 billion in Texas and $8 billion along the Gulf Coast to build energy plants and export facilities in recent years.)

Qatar never left Graham’s relationship to chance. In 2018, Barzan began paying $75,000 a month to a lobbying firm led by Christopher Ott. Ott and his colleagues met regularly with Graham and his staff to discuss Barzan and the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities being developed in South Carolina.

On the day of the 2023 Hamas attack, Graham took a phone call from Andrew King, a former deputy chief of staff to the South Carolina senator whose firm earns $50,000 a month as a lobbyist for Qatar’s embassy in Washington. Graham and King talked or met seven more times by the end of December, including the day when Graham stepped onto that hotel stage in Qatar.

Graham and King didn’t respond to questions from The Free Press. The lobbyist said in a government filing that they always talked about “U.S.-Qatar relations.” Graham told the Doha audience that Qatar is “more the solution than the problem.”

Al Jazeera and Influence Campaigns

American newsrooms are meant to be above the political fray. Qatari money has still found a way to break through.

In 2019, Qatar was under immense criticism for exploiting low-wage migrant workers involved in building soccer stadiums for the 2022 World Cup hosted by the country. Human-rights groups and European media alleged it was equivalent to slave labor and that thousands died. Exposure of the quid pro quo by The Washington Post embarrassed Qatar.

It was right around that time that the Al Thani family gave $50 million to the conservative news site Newsmax. Newsmax’s founder encouraged staff to soften their coverage of Qatar.

Less well-known is Qatar’s investment in conservative radio commentator John Fredericks, who was vice chairman of Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign in Virginia and active in the 2020 campaign.

From 2017 to 2019, Fredericks’ company, Common Sense Media Holdings, was paid at least $180,000 by the Qatar-America Institute (QAI) to provide “regular show appearances by highly ranking Qatari officials” and to broadcast “live shows every other month at QAI to promote Qatar’s progress,” according to lobbying filings. QAI is a nonprofit organization funded by Qatar’s embassy.

Fredericks told The Free Press that QAI wasn’t registered as a foreign agent while he worked with the organization and reported the payment when it did register.

“My exposure to them was totally apolitical,” he said. “I mean, there was no politics that ever came into play. Even when I had the former ambassadors on, they would basically come on and tell you what was going on.”

Qatar also influences American media through Al Jazeera and a social-media news and storytelling project called AJ+. In 2020, the Justice Department said AJ+ had to register as an agent of Qatar, but Doha’s lawyers and lobbyists are contesting the decision.

For Hamas, Al Jazeera is the ultimate soft-power tool. According to documents shared by the Israeli military last fall, at least six Al Jazeera journalists were active members of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad. Al Jazeera denied the allegations and said the documents were fake.

“Could you imagine after 9/11 if bin Laden and al-Qaeda had a platform like Al Jazeera to shape attitudes toward America in the Middle East?” said Hoffman, the Georgetown professor. “The perception of both the U.S. and the war on terror could’ve been very different.” Al Jazeera didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Hamad bin Jassim Al Thani, a former prime minister of Qatar, said in 2022 that the country “had journalists on our payroll.” “We would pay them every year,” he added. “Some of them received salaries,” and “all the Arab countries were doing this.”

The months after the October 7 Hamas attack presented a pressing PR challenge to Qatar—it had to role-play as an American ally while hosting the leadership of Hamas. It worked overtime to shape its image in the American press. Those efforts included about $570,000 in digital advertising for brand awareness, $170,000 to The New York Times and Clear Channel Outdoor, $110,000 to The Wall Street Journal’s parent company, $60,000 to Google and Meta, and more than $70,000 to NJI Media, a Virginia-based ad agency, for an “advertising campaign,” federal records show.

One of Qatar’s newest lobbyists is a co-founder of Washington Reporter, a newsletter “to provide right-of-center news and commentary to a D.C. audience.” Its founder, Garrett Ventry, is paid $80,000 a month to “promote a positive image” of Qatar, especially “the important role of the State of Qatar in international relations.”

Washington Reporter was started last May and is backed by more than $1 million from prominent funders, including Omeed Malik, the financier of Tucker Carlson’s new media venture. (Ventry resigned from the company’s board and executive leadership team in September after registering as a lobbyist for Qatar.)

Qatar is also positioning itself as a hub for Western news organizations in the Middle East. In February, CNN announced it would open a new “operation” this year in Media City in Doha, which describes itself as “a global hub for media companies” that helps them “in managing every aspect of their journey as they take their next steps to operate from Doha.” Media City has also announced partnerships with The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg Media to stage news events in Doha.

Some journalists have accepted free travel and accommodations from Qatar, which is eager for them to participate in conferences and events sponsored by the country. The events often include speakers who praise Qatar’s role as a negotiator and mediator in the Middle East.

In May 2024, Ali Velshi, the Canadian journalist and MSNBC anchor, interviewed America’s ambassador to Qatar, Timmy Davis, at the Global Security Forum, co-hosted by the Qatari government and the Soufan Center, a global research and events organization headed by a former FBI counterterrorism expert, Ali Soufan.

Velshi, a former anchor at Al Jazeera America, told the room of journalists, diplomats, and policy professionals: “I would argue that everybody in this room understands. . . the role that Qatar is trying to play and is playing in this very serious issue we’ve got in the Middle East right now.”

The Global Security Forum paid Velshi’s travel and hotel costs, and it hosted an event to promote his latest book, Small Acts of Courage. Velshi’s wife, Lori Wachs, is a member of the Soufan Center’s board of directors.

Travel for outside speaking engagements by MSNBC anchors usually is covered by the organizer, according to a person familiar with the network’s practices. A Soufan Center representative said that the Global Security Forum “covers travel costs for some invitees, depending on factors such as the nature of their participation.”

Also there was political and foreign-affairs commentator Steve Clemons, then an editor-at-large for Semafor, a new U.S. media company. Clemons hosts a talk show from Washington for Doha-based Al Jazeera English.

In an interview with one of Qatar’s lead diplomats and negotiators, Clemons said: “We’ve just heard some, I think, very important remarks about Qatar’s decision to be a kind of platform for problem-solving between antagonistic parties around the world, not just in Gaza.”

Conference organizers paid for Clemons and his husband to travel and stay at the event, Clemons told The Free Press. “I don’t, you know, buy everything” that Qatar says, he added. “But I do believe that they play an interesting role behind the scenes in massaging a lot of these things that, you know, we need to solve.” (Clemons left Semafor in June 2024.)

Qatar also relies on its vast network of lobbyists to directly influence media coverage. Sometimes that outreach goes nowhere, or leads to short phone calls or email conversations. Other times it has generated image-related wins for Qatar.

Andrew King, the former deputy chief of staff to Senator Graham, called Bill Bennett twice last July, according to a filing by the lobbyist. The former education secretary for the Reagan administration is now a conservative political commentator.

Four days later, Fox News’ website published an op-ed by Bennett with the headline “An American Education Partnership in Qatar Brings Surprising Benefits to the Middle East.”

Bennett denied in his article that there was a “Qatari influence campaign” on U.S. college campuses. He also promoted “Education City” in Doha, now home to the satellite campuses of six American universities. Bennett didn’t respond to requests for comment to The Free Press.

The Largest Foreign Funder of American Higher Education

Georgetown University, located in the heart of the capital of the free world, is one of the top colleges in the U.S. Its School of Foreign Service produces diplomats, thinkers, policymakers, and leaders, from former CIA director George Tenet (Class of ’76) to U.S. president Bill Clinton (Class of ’68).

So why does Georgetown have a campus in Doha?

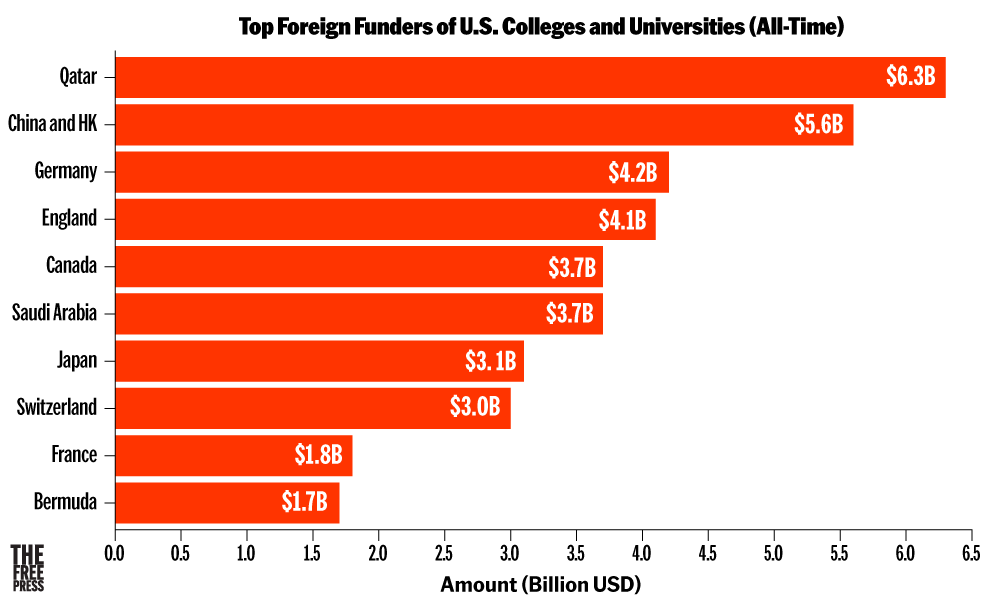

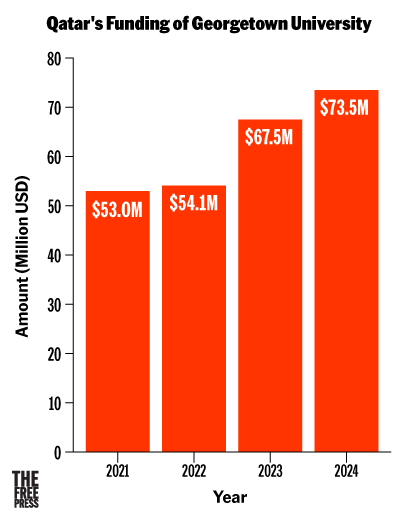

Part of the answer is money. The Qatar Foundation, founded in 1995 by the former Emir of Qatar, gave Georgetown $760 million to open a satellite campus in 2005. And the money from Qatar never stops. From 2021 to 2024, Georgetown received about $248 million from Qatar, according to the Network Contagion Research Institute.

Qatar is the largest foreign funder of U.S. colleges and universities in the world, spending more than $6.3 billion on contracts and gifts since the government started tracking the data in 1986. In comparison, China spent about $5.6 billion, and Saudi Arabia spent $3.7 billion, NCRI said.

Georgetown University in Qatar is located in Education City, a mega-campus that also includes a Cornell University medical school ($1.8 billion), Texas A&M University engineering programs ($700 million), and a Northwestern University outpost that offers journalism and communications degrees ($600 million).

Qatar’s track record on human rights and free expression—it is illegal, for example, to criticize the government or any member of the royal family—is challenging, to say the least.

In 2019, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression ranked Georgetown’s Doha campus among the 10 worst colleges for free speech after the campus canceled a planned debate on God that asked participants to argue whether “major religions should portray God as a woman,” inspired by a pop hit performed by singer Ariana Grande.

The debate’s promotional poster, which featured Grande in place of God in Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam, sparked a wave of backlash on Arabic-speaking social media. Georgetown Qatar said the campus was “committed to the free and open exchange of ideas, while encouraging civil dialogue that respects the laws of Qatar.” Yet “blasphemy,” or criticism of Islam, is illegal in Qatar and punishable by up to seven years in prison.

Bruce Hoffman, the Georgetown professor who taught at the Doha campus for two years, said that he didn’t feel pressure to censor his course materials. But he was shocked to discover some of the students in his class on terrorism studies “doubted whether al-Qaeda was a terrorist group,” he said. The students were mainly diplomats pursuing master’s degrees.

He agreed to teach in Doha because “you’re teaching people and opening them up to different ideas and new perspectives,” he said, but would never do it again after October 7. “Qatar’s largesse enabled the attacks,” he said. “To me, it’s unacceptable.”

Qatar’s influence also trickles down to Georgetown’s main campus in the heart of D.C. Henrik Schildt Lundberg, who graduated with a master’s degree in foreign service last spring, told The Free Press that he and his classmates were invited to a lavish dinner at Qatar’s embassy with Majed al-Ansari, the spokesperson for the Qatar Ministry of Affairs.

When one Georgetown student asked al-Ansari about Qatari human-rights abuses of foreign laborers, al-Ansari responded by accusing the student of “colonialist thinking,” Lundberg said.

Lundberg, who served as a Persian translator for the Swedish Foreign Ministry in Iran for two years before attending Georgetown, told The Free Press that he viewed the dinner as part of Qatar’s strategy to strengthen its image among elite American college students.

“They know exactly which buttons to push and how to phrase an argument, how to engage in conversations with students who are especially progressive,” he said.

Northwestern University art history professor Stephen Eisenman found a lot to be worried about when he visited its Doha campus in 2015. Faculty “enjoy limited academic freedom,” particularly because most of them do not have tenure, he wrote in a report about what he saw.

Students “appear to have internalized many speech restrictions and willingly operate within them,” and the campus struggles even to provide students with books that “violate censorship laws” in Qatar, the report added.

“There is little sign that the regime is becoming more liberal in its attitudes toward speech,” concluded Eisenman, then the president of Northwestern’s faculty senate. “If anything, just the opposite.”

He said he went back home feeling “very dubious. . . about the viability” of Northwestern’s mission to create a Western-style journalism school in Doha.

Eisenman said in his report that he believed the Doha campus “is run at no cost” to Northwestern and that it “makes money from the arrangement, though not very much.” The campus had 470 students from more than 70 countries in the 2024–25 academic year, and its 10-member “joint advisory board” includes Qatar’s deputy prime minister, secretary general, and the executive director of Al Jazeera. Georgetown’s advisory board in Doha includes the ruling emir’s sister.

The Free Press asked Eisenman whether he thinks anything has changed in the past decade. He responded, “I now feel that Al Jazeera is so valuable a source for information about the ongoing genocide in Gaza that Northwestern would be wise to maintain and even expand its affiliation with Qatar.”

Northwestern told The Free Press that its Doha campus is there “to educate future generations of journalists and those working in communications fields, representing more than 50 nationalities, to help positively impact the region.”

A year ago, Texas A&M’s board voted to close down its Doha campus by 2028 after The Free Press reported that the latest contract between the research institute and the Gulf state would have granted the Qatar Foundation ownership of intellectual property developed at the university’s Doha campus.

Texas A&M said that it was “false and irresponsible” to accuse it of sharing any sensitive information with Doha. Texas A&M told The Free Press that it complies with all U.S. laws and rules related to its international relationships, research, and export control. Texas A&M cited regional instability as the cause for the board’s decision to close down the campus in Doha.

Qatar says it isn’t using its money to buy credibility through U.S. colleges and universities. A “briefing pack” created and distributed by the country’s American lobbyists in June 2024 said that even the idea that Qatar is a “major foreign donor to American universities” is a “misconception.”

Qatar doesn’t donate to these schools, the document said. It just pays for the operating costs of the Doha campuses. “There is neither the intention nor the opportunity for Qatar to influence anything that happens on university campuses in the United States,” it said.

Qatar Foundation International (QFI), the U.S. arm of the Qatar Foundation, has given out tens of millions of grants to K–12 public schools to fund Arabic language and culture programs from New Haven, Connecticut, and Amherst, Massachusetts, to Arizona and California.

QFI gave nearly half a million dollars to the Minneapolis Public School District to fund salaries for Arabic teachers. The contracts often stipulate that teachers must attend QFI professional-development training as part of the grant.

Last year, The Free Press reported that QFI donated more than $1 million to the New York City Department of Education from 2019 to 2022, including support for an elementary school in Brooklyn to teach young students Arabic through art. The classroom hung a map of the “Arab world,” which excluded Israel.

The map was removed after The Free Press published its article about the map. In the “briefing pack” distributed by the lobbyists, Qatar said that it was not responsible for the map and that the organization “has no role in setting or influencing classroom content or management.”

Federal laws require colleges to report all gifts and contracts from foreign entities that exceed $250,000. Smaller contributions are much harder to track.

The Free Press reviewed emails from 2016 between Craig Cangemi, a program officer at QFI, and Emma Harver, a program coordinator for a joint program between the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University for the study of the Middle East.

The emails describe a conversation between Harver and her supervisor about how public universities might be cautious about “taking QFI funds.”

“He thinks that some Title VI institutions might be wary of accepting money,” she wrote, and “because we are government-funded, we are often scrutinized on how we spend our money and our other funding sources.”

She told the Qatar official that her boss “thinks that non-Title VI funded programs (and especially private institutions) would be happy to apply to QFI for grants.”

In the same email, Harver thanked Cangemi for QFI’s support of UNC’s “Learning through Languages research symposium,” and then added, “and glad that we were able to accept this money via Duke.”

UNC’s Center for Middle East and Islamic Studies denied ever receiving any funding from QFI and said it “had no role in the academic content” of the event, which met the joint program’s “high scholarly standards.” Cangemi and Harver didn’t respond to requests for comment from The Free Press.

If the college leaders who accept so much money from Qatar ever feel nervous about how that looks, they avoid showing it. Last month, Georgetown and Qatar announced an agreement to renew their Doha partnership for 10 years.

Georgetown’s interim president, Robert M. Groves, also bestowed one of its highest honors on Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, the mother of Qatar’s emir and chairperson of an educational nonprofit that has funneled millions of dollars into U.S. schools. The award “is reserved for individuals whose contributions reflect the university’s deepest commitments,” Groves said.

Left unmentioned was her praise of Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, mastermind of Hamas’s October 2023 massacre.

A Scandal in Plain Sight

At present, Qatar’s influence in Washington is arguably at its strongest point since its independence in 1971. In amassing this power, Qatar’s government has denied paying any bribes and seems undeterred by any criticism of anything it does. In late March, Middle East experts in Washington were stunned when Roger Marshall, a senator from Kansas, pounced on Charles Asher Small of the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy during a hearing about antisemitism. Small had criticized Qatar for its support of Hamas and its ties to Iran and Afghanistan.

“It’s interesting, the prejudice that I hear coming out of your mouth,” Senator Marshall said. “Of the 120,000 people evacuated from Afghanistan. . . 60,000 of them came through Qatar. Without Qatar, we would have had thousands more deaths.”

In 2019, Marshall said that Qatar’s “blind eye” to terrorism undermines American security and calls into question the long-term security partnership of the U.S.-operated base in the Gulf country.

What changed his mind about Qatar? Starting in 2022, lobbyists for Qatar began contacting his office and invited him to visit Qatar, lobbying records show. The lobbyists helped pay for Marshall’s meeting in Doha with Qatar’s ruler in 2023, and they emphasized Qatar’s role in helping to evacuate Americans caught in Afghanistan with Marshall’s chief of staff.

When asked by The Free Press if Marshall’s comments at the hearing were drafted or shaped by lobbyists for Qatar, a spokeswoman said: “In agreement with both President Trump and Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff, Senator Marshall believes that Qatar has proven itself to be a key and strong ally to the United States in the Middle East over the last several years.”

Those aligned with Qatar will argue that the country is a force for stability in the Middle East and a diplomatic partner that is more transactional than ideological. They’ll admit that Al Jazeera is a problem, but insist that the Al Thanis are committed to liberalizing their society, but must go slowly.

These supporters believe that the U.S.’s relationship with Qatar allows Washington to limit its involvement in the region in a way that is more sustainable than it has been in the past.

They note, among other things, the crucial role Qatar played following the 2021 Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, when more than a third of the people evacuated by the U.S. transited through Qatar. Doha’s relationship with the Taliban—the Qataris hosted the Taliban’s political office from 2013 to 2021—also helped Qatar conduct its own evacuations and secure safe passage through the chaotic and terrorist-laden Kabul airport. Qatar’s supporters also point to the country’s role as a mediator between Israel and Hamas; Doha has been the principal facilitator of hostage-release and ceasefire deals between the two parties since the October 7 massacre.

Perhaps these supporters of Qatar and the Al Thani family will be proven right. Perhaps Qatar will liberalize and bring the region along with it. Perhaps Qatar will join with Saudi Arabia and the UAE to emphasize education and investment above ideology and extremism.

But what’s at stake is nothing short of American sovereignty and national security.

At a moment when so many political leaders, pundits, and ordinary Americans are reaching for explanations of—or entertaining conspiracies about—who really pulls the strings in Washington and beyond, many of them are ignoring a story in plain sight.

The Free Press’s Danielle Shapiro contributed to this report.

Comments are closed.