DAVID HAZONY: THE ANTI-SEMITISM WE NEVER TALK ABOUT

When a large number of foreign-policy experts—both Republicans and Democrats—falsely attribute many of the world’s ills to the Jewish state, they are channeling an ancient hatred. The time has come to say so.

Schizophrenia is a much-abused metaphor. Those of us who have ever cared about someone who suffers from the illness have a hard time with all those pundits who get it wrong, confusing it with split-personality disorder, and then applying it metaphorically to anybody who carries two contradictory thoughts.

But knowing about the disease can still be helpful in talking about politics—giving us a much better metaphor to describe the conversation about Israel taking place in Washington today.

Schizophrenics suffer not from multiple personalities, but from an inability to tell the difference between things they encounter or imagine on the one hand and reality on the other. It’s been described as a kind of filtering problem: If they overhear someone on television saying, “the court awarded me $5 million,” a schizophrenic may easily believe she is owed that money and say so repeatedly for years. Schizophrenics also suffer from all manner of delusions, believing things happened that never did. And if they are also paranoid, they will try to convince you that secretive people and forces are conspiring to hurt them.

I can’t tell you how often I have been made to feel like many of Israel’s critics suffer from this disease—or at least are eager to imitate it with shocking fidelity. The use of words like “apartheid,” “genocide,” or “ethnic cleansing” to describe a country that I and millions of other educated, sensitive human beings have visited and lived in without noticing anything resembling South Africa, Rwanda, or Kosovo—a regular Western democratic country I have traveled through, including in the very territories and checkpoints and settlements some are insisting I am in denial about—is on the face of it silly, and remains so no matter how many people repeat it.

Except that schizophrenia is not silly. It is tragically debilitating in countless ways, not the least of which is that the patient rarely admits anything is wrong, and therefore lacks the means of getting help. A political discourse that cannot distinguish reality from fantasy is forever at a loss, taken aback by tragedies that follow one another like blinding winter storms—and ultimately will find themselves at the mercy of those who control the fantasies, spelling the end of anything resembling responsible self-rule. Building your worldview on facts, not just feelings, is deadly important.

And for Israelis, in particular, the fact that fantastical claims about their country run rampant around the world is especially damaging. You may say what you will about the decline of anti-Semitism after the Holocaust, but today Israelis remain the only sovereign people whose very existence continues to be a delicate question, the greatest target of enlightened venom in polite Western circles, and the only country the hatred of which crosses civilizational and economic and cultural and class lines. Anti-Semitism may have morphed and modernized, but it continues to menace.

There has, of course, been some progress in identifying the newest forms of anti-Semitism and seeing it for what it is. In recent years, two major lines of attack on Israel have been revealed to be essentially anti-Semitic tropes, repackaged for a modern audience.

One was the claim, preposterous to anyone with an honest heart and a historical eye, that the vicious anti-Israel protest movement (of which the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement is only a part) had nothing to do with anti-Semitism. But in the wake of a decade of efforts, most famously spelled out in Natan Sharansky’s “3D test” (demonization, double-standards, delegitimization) to assess whether a given criticism crossed the line, the association of anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism has become much discussed—including in pronouncements by Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper and French Prime Minister Manuel Valls in the past year.

The second was the ancient trope of dual loyalty—that the Jew is never fully committed to his countrymen—which in our time was modernized through the concept of the “Israel Lobby,” made most famous by the essay and book of that name by Stephen Walt and John J. Mearsheimer. Here the claim was that by focusing on the network of organizations that advocate for Israel—most centrally AIPAC—you can discover why American foreign policy is so supportive of Israel when it so obviously shouldn’t be. Yet while this view still has adherents, others have worked hard to point out that the pro-Israel lobby is actually only a fraction of the size of the anti-Israel lobby, which has been catalogued in books as well as more recent press reports about the influence that foreign governments have on Washington; and that while the anti-Israel lobby is heavily funded by foreign governments, the pro-Israel efforts have been built almost entirely on the strength of American taxpayers legitimately advocating their foreign-policy beliefs, and a broader American public that is very pro-Israel. The Israel Lobby was successful not because it was fair-minded or objectively interesting, but because it found a creative way to project the classic charge of dual loyalty onto the modern political landscape.

But there is a third, core premise of anti-Semitism that has been modernized—deeper and harder to see, but all the worse for it. Barely anyone has gone out on a limb to identify it as such, because to do so is to implicate an awful lot of very important people in something that sounds quite nefarious. But this idea has found its way into the most influential halls across the Western world and, decisively, in Washington, where I have spent the last two years trying to understand why American policies so often fail to mirror the support for Israel that repeated polling confirms is held by the great majority of Americans on both sides of the aisle.

It is the classic anti-Semitic myth of the conspiracy—that Jews hold the keys to a very large part of what ails the world, and that if we just could somehow get rid of the problem, we would all be better off. In the 1920s, the great industrialist and vicious anti-Semite Henry Ford had no qualms about laying out the map and methods of Jewish domination as he saw it.

The motion picture industry; the sugar industry; the tobacco industry; fifty per cent or more of the meat packing industry; over sixty per cent of the shoemaking industry; most of the musical purveying done in the country; jewelry; grain; cotton; oil; steel; magazine authorship; news distribution; the liquor business; the loan business; these, to name only the industries with national and international sweep, are in control of the Jews of the United States, either alone or in association with Jews overseas…. [People say] “The British did this,” “The Germans did this,” when it was the International Jew who did it, the nations being but the marked spaces on his checker board.

Because it is so difficult to disprove—Jews are indeed influential far beyond their numbers, and conspiratorial claims are all about suggested implications of outsized influence and “connecting the dots”—the Myth of Jewish Centrality has been one of the most harmful features of anti-Semitism, and not just over the ages but especially in the tortuous 20th century. Adolf Hitler reportedly had a life-sized picture of Ford next to his desk.

In the modern reinvention of the idea, however, it is not the Jewish people but the Jewish state that is the core problem in the world, the key obstacle to betterment.

The claim takes different forms and has long been fueled by the propaganda juggernaut of the Arab world. By the time it reaches the softer shoals of places like Foggy Bottom, of course, it goes through a filtration system of bureaucratic qualifiers. Not Israel as a whole is to blame, just the “policies of the current government,” though the policies in question have been exercised by all Israeli governments since 1967; Israel is a wonderful ally, but the “Occupation” is the core problem, though Israel’s diplomatic standing was significantly worse prior to the conquest of Judaea and Samaria; perhaps not all the world’s problems will be solved if Israel were to back down—just a lot of them, or just for the Middle East, or for American interests; and so on.

What all of these have in common is that despite the qualifiers, the Israel problem inevitably is inflated so radically, a twisted causality attributed, an implication that if only this problem—not Iran or Russia or North Korea or Syria or Europe’s immigrant crisis or anything else—were solved, then we’d all be having a lot more fun. Israel rises to the top of the agenda as a problem to solve—despite the fact that Israel has already forged peace with its two largest neighbors as well as a tacit alliance with the region’s most important American ally, making the whole “Arab-Israeli conflict” phrasing into a relic; despite the fact that all the decades of this conflict have claimed only a tiny fraction of the lives lost in neighboring Syria in the last five years alone; despite the fact that every single armed conflict Israel has faced in the last decade has been caused not by Palestinian suffering but by Iranian proxies initiating attacks on peaceful civilians while Tehran clandestinely works to build a nuclear bomb.

And usually, given the proclivities of the American electorate, the claim is further tempered by coupling together Israel with the Palestinians into a single problem, into a formulation that sounds something like these words spoken in 2010 by former U.S. Ambassador to Israel and Assistant Secretary of State Edward Djerejian, who today heads the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, named after former Secretary of State James Baker:

Obama cannot remove himself from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict because this issue affects the United States’ core national security interests. The Arab-Israeli conflict, and especially the Palestinian issue, remains one of the most contentious and sensitive issues in the entire Muslim world. Osama bin Laden exploits the plight of the Palestinians, as does [Iranian President Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad … This has a direct influence on the United States, which is expending its blood and treasure fighting insurgencies in overwhelmingly Muslim Iraq and Afghanistan.

We would be naive to think that resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict will eliminate the problems of terrorism and radicalization in the Islamic world, but it will go a long way toward draining the swamp of issues that extremists exploit for their own ends.

Or consider the words of Zbigniew Brzezinski, the National Security Adviser under President Jimmy Carter and luminary of the “realist” school of American foreign policy. This is what he had to say in 2004, after the United States invaded Iraq, in a war that (except according to some really weird websites) had nothing to do with Israel whatsoever:

The United States must recognize that success in Iraq depends on significant parallel progress toward peace between the Israelis and Palestinians. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the single most combustible and galvanizing issue in the Arab world. If the United States disengages from Iraq before making significant headway toward settling that dispute, it could face a sovereign Iraqi government that is militantly hostile to both Israel and the United States.

Others take it further. Chas W. Freeman, Jr., the former U.S. Ambassador to Saudi Arabia who in 2009 was very nearly put in charge of interpreting all U.S. intelligence for the Obama administration, wrote these frankly outrageous words in 2011:

Israel has nonetheless also demonstrated that its hold on domestic U.S. politics remains unbroken. This past year, it was able to compel our president to swear allegiance to expansive Zionism and to repudiate policies endorsed by his own and previous administrations as well as the international community. By contemptuously overriding the views and interests of the United States in this way, Israel and its American claque debased and discredited American international prestige and regional credibility. As a consequence, the world has come together in a series of ever firmer votes of no-confidence in U.S. leadership and diplomacy on the Israel-Palestine dispute. American military might remains unchallengeable, but the power of the United States to protect Israel from the political and legal consequences of its policies, statements and actions has been gravely impaired. This is a perverse result for an Israeli government and its supporters to have engineered…

The perceived need to counter Israeli and American policies is already throwing together some strange diplomatic bedfellows. It is also marginalizing American influence on other issues of concern in West Asia and North Africa. The regional clout of non-Western powers like China, India, and Russia will surely grow concomitantly.

Israel, we learn, is to blame not only for giving Islamic extremists an excuse to violence as Djerejian claimed, but for the overall American decline under the Obama administration.

These are only a few quotations from people who apparently felt a lot freer to speak after they were out of office. But the Myth of Centrality is so pervasive that many Washington insiders take it for granted because they have heard it so often from so many directions. Any genuine familiarity with the Middle East, especially in the past few years, reveals the obvious falsehood of the claim. But we should not expect the intellectual heirs of Henry Ford to modify their views just because a few facts have gotten in the way.

Of course, I am not the first person to point out how widespread and influential is this Myth of Centrality. A recent essay by former Deputy National Security Adviser Elliott Abrams calls it the “epicenter theory,” based on comments by President Obama’s first National Security Adviser James Jones, who in 2009 described the Israel-Arab conflict as the “epicenter” of world politics. “Finding a solution to this problem,” Jones continued, “has ripples that echo, that would run globally and affect many other problems that we face elsewhere in the globe.”

This view, Abrams points out, “has always been nonsense,” but because it has been the principal excuse that Arab and Iranian tyrants have deployed for decades in order to justify the oppression of their own peoples and their distracting belligerence towards Israel, one can understand why some Western leaders, wanting to impress such governments rather than confront them, might choose to repeat the lie.

Lee Smith, whose 2011 book The Strong Horse: Power, Politics, and the Clash of Arab Civilizations has become a central text in understanding the region’s unique political dynamic, probably made the most substantial effort to trace this pattern in 2010, when in an essay in Tablet he described what he called “linkage”—i.e., the ideological commitment to connecting all middle-east conflicts back to the single source conflict between Israel and its neighbors. As Smith wrote:

This is the one idea that has won the support of a broad consensus of U.S. congressmen, senators, diplomats, former presidents, and their foreign-policy advisers, seconded by journalists, Washington policy analysts… the central role that U.S. Middle East policy has given to the belief that, from the Persian Gulf all the way to Western North Africa, a region encompassing many thousands of tribes and clans, dozens of languages and dialects, ethnicities and religious confessions, the Arab-Israeli issue is the key factor in determining the happiness of over 300 million Arabs and an additional 1.3 billion Muslims outside of the Arabic-speaking regions. Where does such an extraordinary idea come from? The answer is the Arabs—who might be expected, in the U.S. view of the world, to give us an honest account of what is bothering them. However, this would ignore the fact that interested parties do not always disclose the entire truth of their situation, especially when they have a stake in doing otherwise.

Smith’s view is in some sense a charitable one—for he claims that Western policymakers who accept “linkage” are merely credulous of Arab propaganda. But beliefs about faraway places are often dictated by convenience and habit rather than evidence, even at the highest levels, and some ideas retain their ancient pull even after history disproves them, as it did with the oil crisis of the 1970s, the Iranian revolution and its implications, the Beirut debacle, the Gulf War, September 11th, and the Iraq mess—a generation-long period during which Israel’s standing in the region improved, arguably, more than America’s did.

One person who has recognized just how deeply held, widely disseminated, and debilitatingly distorting this Myth of Centrality has become is Michael Doran. A former top official at the Pentagon and the National Security Council in the George W. Bush Administration and acolyte of the historian Bernard Lewis, Doran was a senior scholar at the Brookings Institution for years before recently decamping to the Hudson Institute.

When I first came to Washington in early 2013, I wrote a piece for The Tower in which I posed a challenge to those long-time Washington “realists” like Brzezinski and former National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft, who have always claimed that the U.S. should tailor its foreign policy according to its colder interests (i.e., oil and therefore the Arabs) rather than sentiments (i.e., shared democratic values and therefore Israel). To my mind, the Arab world had become so unstable by then, and Israel had become so economically and strategically successful, that supporting Israel seemed to make much more sense even according to a strictly interest-driven calculus.

Before I published the piece, however, I sent it to Doran, and he called me up. “I liked everything you wrote,” he told me, “except your definition of realists. Realists are just people who think Israel is the source of all the problems in the Middle East.”

I ignored him and went ahead and published the piece without modification—and then history proved him right. For even as my overall assessment of the region only grew more acute with the collapse of oil prices, the rise of ISIS, and the implosion of several countries, the realists continue to look for ways to push American foreign policy in contravention of Israel’s interests, whatever they may be. You see, nobody ever imagined that the needs of the Gulf states would align so closely with those of Israel. But when the time came, and the Iranian threat became big enough to push former rivals into an apparent alignment, the realists happily threw their long-time OPEC friends under the bus and supported the Iranian entente.

What was important to the realists, it turned out, was not whom they were for, but whom they were against.

But while Abrams, Smith, and Doran, as well as others like Tony Badran, have delineated both the widespread acceptance and absurdity of the Myth of Centrality (or “epicenter theory” or “linkage”), little discussed has been its connection with anti-Semitism—in no small part because of the implication that a significant segment of the foreign policy establishment in the United States and elsewhere would be cast, to a greater or lesser degree, as anti-Semitic, even if only in effect but not intent.

I do not mean to suggest that every person who believes in the Myth of Centrality to one degree or another, or who promotes different parts of it, is an anti-Semite. Being an anti-Semite is different from holding opinions that happen to fall into an ancient logic associated with anti-Semitism; it is different from unwittingly contributing to a spreading global narrative that offers horrible and unpredictable outcomes for Jews; it is certainly different from echoing the sentiments of leaders hoping for a peaceful two-state solution in our time; it is arguably even different from calling for Israel to become an enlightened “binational state” or for the Jews to “get the hell out of Palestine” and return to Europe, as Helen Thomas, one of Washington’s veteran political journalists, did not so long ago. I do not claim to know what people are or think privately, and I assume most people do not realize the hidden historical vibrations emanating from their own mouths.

And yet, it is very difficult to avoid the conclusion that the Myth is itself a central part of the broader anti-Semitic argumentative web, and therefore crucial to its current energy. For what else are we to call a belief that puts the Jewish state at the center of the world’s problems despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary?

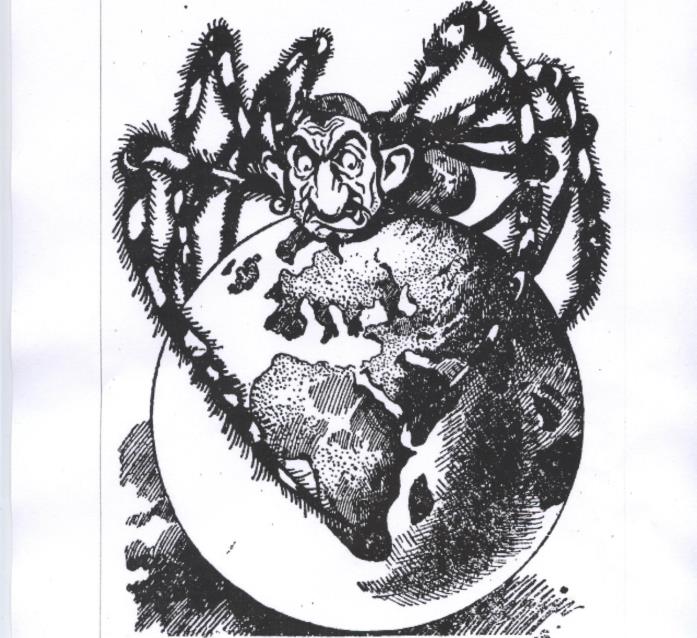

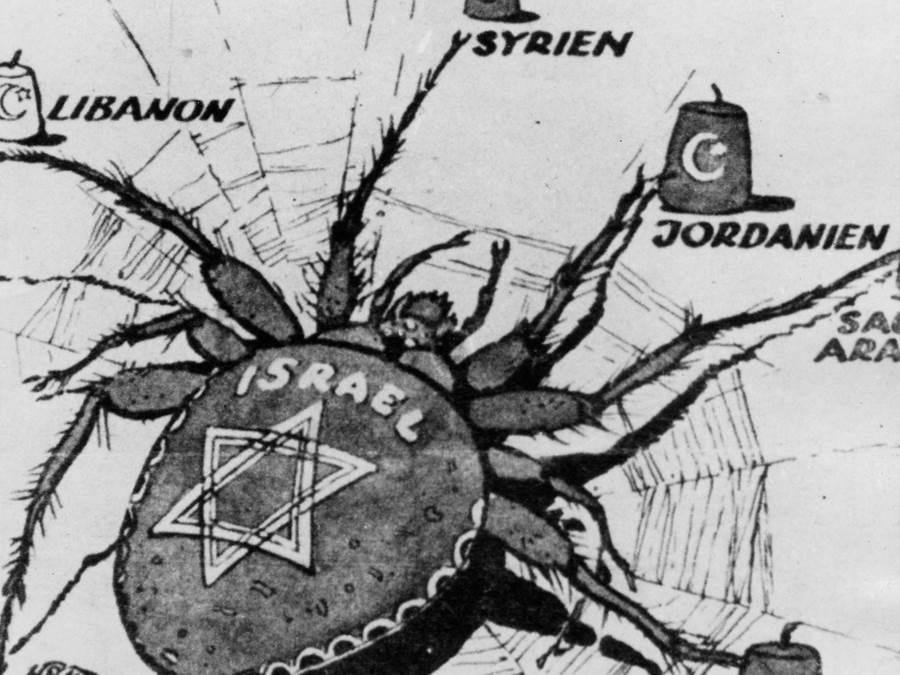

Just as anti-Zionism is a form of anti-Semitism because it’s every bit as mean-minded, violent, rabid, and riddled with demonization, double-standards, and delegitimization as the old version, it is not hard to see how the Myth of Centrality fulfills a different yet no less important aspect of classical anti-Semitism: The belief in the Jew’s ubiquity, his power, his schemishness, his wickedness, and consequently the implicit yet necessary connection between defeating the Jew and saving the world. In classical anti-Semitism, the Jew was the cosmic pivot around which evil spun, the multi-tentacled black hairy creature that corrupted the world’s morals and pulled the strings of its economy, earning hatred and fear but never respect. In the modern variety, it is solving the problem of the Jewish state that holds the keys to world peace, to Western interests, to an end to the strife and murderousness and collective outcry that dominates our news. And in refusing to take the simple steps necessary to end the conflict—for if they are so smart, it must be their choice, yes?—these empowered Jews hold the entire world hostage.

I mentioned earlier how the “Israel Lobby” myth recalls the classic anti-Semitic trope about dual loyalty. But that’s inside the United States. Abroad, it combines with the Myth of Centrality to create a powerful assertion of Jewish conspiracy to thwart peace in the most globally impactful ways. And one gets the sense that people are getting less reluctant to say so.

Take, for example, the statements of former British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw just last year at the Round Table Global Diplomatic Forum held in the House of Commons. Apparently unaware of the Israeli ex-parliamentarian in the room with a cell phone, Straw began dilating on the “unlimited” funds available to Jewish organizations, and the German “obsession” with defending Israel—both of which he counted among the biggest obstacles to peace today. Predictably, the comments triggered nothing less than rapture in the anti-Semitic scribblings of David Duke and the anti-Zionist emissions of Mondoweiss. “It is amazing that ideas that were once blacklisted as being anti-Semitic,” effluviated the site’s founder Philip Weiss, “are coming more and more into the mainstream… It is a necessary discussion.”

To be fair, Straw later denied having used the specific words attributed to him. But to be fairer still, in explaining what he did say, the only source he cited in his defense was Walt and Mearsheimer’s essay, “The Israel Lobby.”

Another thing that has made it difficult to see the Myth of Centrality as an anti-Semitic trope is the ease with which it enters, under the cover of good intentions, into mainstream, non-anti-Semitic conversation. After all, once you dilute the claim by making it not the Jews but “Israel-Palestine,” and not a question of blame but of priority, then a great many Israelis and Jews are tempted to read it not as anti-Semitism at all, but much the opposite. After all, for Israel the Palestinian issue is indeed very central. And who could object to what appears to be a flattering degree of attention to our problems? Thus when then-candidate Barack Obama appeared on Meet the Press in 2008, nobody thought it problematic when he declared that

If we can solve the Israeli-Palestinian process, then that will make it easier for Arab states and the Gulf states to support us when it comes to issues like Iraq and Afghanistan. It will also weaken Iran, which has been using Hamas and Hezbollah as a way to stir up mischief in the region.

This was, of course, absurd, as President Obama’s administration would make clear. Soon after George Mitchell declared in 2011 that “there has never been in the White House a president that is so committed on this issue,” it became clear that in fact Washington is doing very little to “solve the Israeli-Palestinian process,” and has all but abandoned the cause of weakening Iran or even mentioning Hamas and Hezbollah. This year’s State of the Union address did not even mention the peace process, and though I may not like where he’s taken the Iran relationship, it does seem that the President has lost patience with the obviously twisted Myth of Centrality.

Yet this does not mean the Myth has really faded in Washington. When John Kerry was testifying during his confirmation hearings as Secretary of State only two years ago, he felt entirely natural throwing this into the mix, with the attendant qualifiers:

The President understands the stakes and the implications in the Middle East. And the—almost—I mean so much of what we aspire to achieve, and what we need to do globally, what we need to do in the Maghreb and South Asia, South Central Asia, throughout the Gulf, all of this is tied to what can, or doesn’t happen with respect to Israel and Palestine. In some places, it’s used as an excuse. In other places, it’s a genuine deeply felt challenge.

Yet by now the Secretary of State must understand how little such overfocusing actually ends up benefiting the Palestinians. If anything, this specific kind of global radical attention paid to Israel-Palestine, with the help of people like Zbigniew Brzezinski and Edward Djerejian and Chas Freeman, and with the generally well-meaning cooperation of the media, has made it virtually impossible for any Palestinian leader actually to make the basic concessions required to formulate a pragmatic and permanent two-state peace deal in the territories under discussion. Maps may come and maps may go—but how could any Palestinian leader concede to Israel’s insistence of recognition of the Jewish state when all his Western friends insist that the Jewish state is itself the central problem undermining world peace?

Nor does it actually make any sense that “settlements” are the cause of the problem, as is said so often, rather than a permanent rejectionism on the part of the Palestinians, egged on largely by political hatred of Israel coming from various sectors in the Arab and Muslim world, and key voices in the West, for generations. Leave aside the question of whether Israel should or should not build towns in territories under dispute—for my point is no less true if you believe Israel is making a tragic mistake in its ongoing settlement policy. Seriously ask yourself which of the following theories makes more sense: That a democratic country that repeatedly has elected governments committed to a two-state solution, frequently attempting to conduct serious negotiations behind the scenes and openly calling for unconditional negotiations, a country in which the population overwhelmingly is dissatisfied with the military occupation of the West Bank to the point of developing an entire elite artistic and literary and political system dedicated to exploring how awful it is and how much they wish for peace, a problem-solving country that has shown more grit and creative energy than any other Western country—that this nation somehow just can’t find the creative moxie to solve it?—or alternately, that the other side, the side that calls for destruction rather than coexistence, the side that has no qualms about celebrating as martyrs those children who kill themselves in order to kill our own children, a combination of kleptocracies and brutalocracies and certifiable RICO cases, including no small measure of Islamic radicals dedicated to the destruction not only of Israel but also America and the entire democratic world—that they simply do not want peace?

I have in the past been accused of ignoring the Palestinians, which is inane—no Israeli can ignore the Palestinians, though Israelis vary dramatically in their level of sympathy towards their political aims. But my accusers never seem to ask themselves what compels them to write about this conflict as opposed to others, to unleash their venomous resentments at the blue and white flag, to habitually, obsessively report on every Israeli headache as if it were a migraine and every migraine as if it were an aneurism. Is it because of the Holocaust? The memory of Western impotence in the face of murderous evil and the need to make sure the Jew doesn’t become the Nazi? (Israelis will be forgiven for seeing the Holocaust more as a memory of Jewish impotence in the face of a murderous enemy.) Yet it is hard to pin this on the Holocaust, for that itself was enabled in no small measure by the very same Myth of Jewish Centrality that we see arising anew in full force through the Myth of Israeli Centrality.

This is not a modern thing, and surely we who know a little history cannot ignore the feeling, the sense that every time somebody says If only Israel were to stop holding America in its grip, were to stop imposing itself on Europeans, were to stop the settlements and the occupation, were to just stop, to give up and give in and restore the Jews to their natural and rightful place as wanderers and quintessential sufferers—if only this, then everything would be better—every time we hear that soft and wistful psalm, we know it is not new, and it is not good.

The Myth of Centrality has not faded here in Washington, but I do believe that the events of the past year have finally made it possible for fair-minded people to recognize what has always been true: That the Middle East is a place where radicalized violence and interpretive schizophrenia are the norm rather than the exception, that belief there largely follows not facts but fears, that the forces of political Islam (or jihadism, as Hillary Clinton fairly calls it) will not rest until every democratic country on earth is replaced by an Islamic State or Islamic Republic, and that Israel—by virtue of its being not Jewish but democratic—happens to be the first in the line of its fire, the greatest magnet of its ire and embarrassment to its claims of supremacy, and the most immediate threat to the grand lie that undergirds every single tyrannical regime on earth.

Yemen is not because of Palestine. Syria is not because of Palestine. Libya is not because of Palestine. The Iranian revolution, the Iran-Iraq war, the rise of Al-Qaeda, the rise of Boko Haram, the rise of ISIS—none of these would have been even slightly dampened by the absence of conflict between the Jordan and the Mediterranean. Without taking anything away from the principle of Palestinian self-determination, any historian will tell you that the Palestinian national movement was a latecomer to the Middle Eastern bloodbath, not really a big thing until the early 1960s (yes, before the Occupation), when Arab governments saw in it an eager and explicit echo of the successful removal of the French from Algeria—a bloody conflict that had nothing to do with Palestine, but which made the profound error of assuming that the Jews were like the French, foreigners who could just “get the hell out of Palestine” when in fact they were making their ultimate historical stand, a Third Act completely different from the rest of their history. Viciousness and barbarism and the permanent preference of political pride over prosperity and peace—these are the hallmarks of the Middle East, and they do not stop being so just because we are sick of hearing about people dying or are looking for new ways to blame the Jew.

And Charlie Hebdo was not because of Palestine. Who thinks it was? Jimmy Carter, for one. When Jon Stewart asked him whether the attacks in Paris this January were caused by something other than ideological extremism, the very first words to come out of his mouth were:

Well, one of the origins for it is the Palestinian problem, and this aggravates people who are affiliated in any way with the Arab people who live in the West Bank and Gaza, what they are doing now—what’s being done to them. So I think that’s part of it.

And before you dismiss him as the dotty ex-POTUS who spouts crazy commentary at every opportunity, please recall that he is currently sitting at the global core of the tone-setting eminences-grises, a founding member of the creepily-named “Elders” group founded by Nelson Mandela that also includes non-slouches like Desmond Tutu, Kofi Annan, and Mary Robinson, the last of whom has been responsible for turning the UN’s human rights effort into a sham of perpetual slander of the Jewish State at the expense of all the other atrocities happening on our planet.

(The Elders, it should be said, claim to be “committed to promoting the shared interests of humanity, and the universal human rights we all share,” but curiously there are only three region-specific subject areas featured prominently on their website. The first of these is Iran, where the goal is not to fight against human rights abuses or the execution of women, or to stanch the terrorism that spews from its loins, or to prevent its getting a nuclear weapon, but instead to “support greater openness and dialogue between Iran and the international community, and encourage Iran to play a stabilizing role in the wider Middle East.” The second is “Israel-Palestine,” which offers the uncontroversial goal of “encourag[ing] all parties to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict who are working for a lasting, just peace.” And the third is Myanmar, an odd choice of a country that gets virtually no media attention, and whose appearance there seems to be meant to dilute rather than advance their central message.)

But the most important thing we need to recognize when we step back and look at the words and deeds of Jimmy Carter and Mary Robinson and Chas Freeman and Edward Djerejian and Jack Straw and Zbigniew Brzezinski and all the others is not just that Israel is not now and never was the real source of trouble around the Middle East, but that to maintain such a belief today, in the face of so much evidence to the contrary, can only be ascribed to precisely the same form of political irrationality we began with—specifically the clinical need to find a single scary cause behind everything.

Sometimes, of course, hateful crazy-talk is motivated not by political ideology but a more base intention of just being hurtful. Many years ago, when I was more observant than I am today, I stood in line in a store in Washington Heights, New York, wearing a kippa on my head. This was in the 1990s, when public acts of kindness were rare and racial tensions were high. I was young. A teenage Hispanic girl with big eyes, in front of me in line, asked if I could hold her spot as she ran to get one more item. I obliged. When she returned, however, an elderly African-American woman who had subsequently queued up behind me was furious that I had let the girl cut back in. She determined to cause me pain matching the injury I had caused her. She found a formula.

“That’s what Hitler did,” she seethed.

Seriously, those were her words.

Today we would call such words “hate speech,” or bullying, or anti-Semitism. One need not declare one evil trait or another of Jews to be guilty of anti-Semitism—it’s enough to be dedicated to hurting Jews as such.

But is that really any different than what people who actually are familiar with the facts are doing when they use words like “genocide” or “war crimes” to talk about Israel? When they look at a liberal society struggling to defend its citizens against terror attacks, and all they can say is “That’s what Hitler did”?

One last point about schizophrenia. In many jurisdictions, the law holds that you cannot really do anything to a schizophrenic until they endanger somebody else. In our world, however, the Myth of Centrality is a perennially brutal thing, no matter how nice a face one puts on it, in part because of the radically unjust burden it places on Jews and Israelis for the ills of the world—but far more because of the neglect it enables everywhere else. It seems we are way beyond the point where intervention is indicated.

The first step is to call it by its name, and although I really do not bandy about the anti-Semitism label lightly, and have written very little on the topic, this is not just a case of somebody disagreeing with me or not liking Israeli manners or being misguided or duped or bought by foreign powers. It is a malady that threatens not just the Jewish people and their state but the integrity of the Western political mind as a whole, and it daily undermines the capacity of liberal democracy to genuinely make the claim that it is somehow different and superior to all the other truth-warping idolatrous regimes history has encumbered mankind with.

So for the sake of our collective aims, our collective hopes, and above all our collective sanity, let us apply the label where it sticks, and bury the anti-Semitic Myth of Centrality once and for all.

![]()

Banner Photo: Zach Kowalczyk / flickr

Comments are closed.